Higher gene interconnectivity allowed for the diversification of animal forms

While scuba-diving in the ocean, it’s possible to spot an array of animals in their natural habitat. Some may be vertebrates, which have a backbone like manatees and sea turtles, whereas many are invertebrates, backbone-lacking creatures like octopi and jellyfish. Some invertebrates may be harder to spot, like lancelets, which are invertebrates that burrow themselves in the sand and filter-feed on plankton. Evolutionary biologists determined that vertebrates evolved from an invertebrate ancestor around 500 million years ago and early in vertebrate evolution there were two genome duplication events. This increased the complexity and genome size of vertebrates, possibly allowing for the increased diversity of vertebrate body sizes, shapes, and other physical features. But researchers are still wondering how exactly this increase in gene number led to this diversity – it may have something to do with how much the genes are regulated.

During embryonic development in vertebrates, the backbone is derived from the notochord, a flexible rod running from the head to the tail that provides structural support in the early embryo. All animals that have notochords are related in one evolutionary group. This includes vertebrates as well as two groups of invertebrates: tunicates, such as sea squirts, and our burrowing friends, the lancelets. In tunicates, the notochord is transient and disappears once the animal becomes an adult. Lancelets have a notochord for their entire life cycle, but in contrast to vertebrates, it never develops into a backbone. For this reason, lancelets are thought to be the closest living relatives to vertebrates and thus can offer key insights for vertebrate evolution.

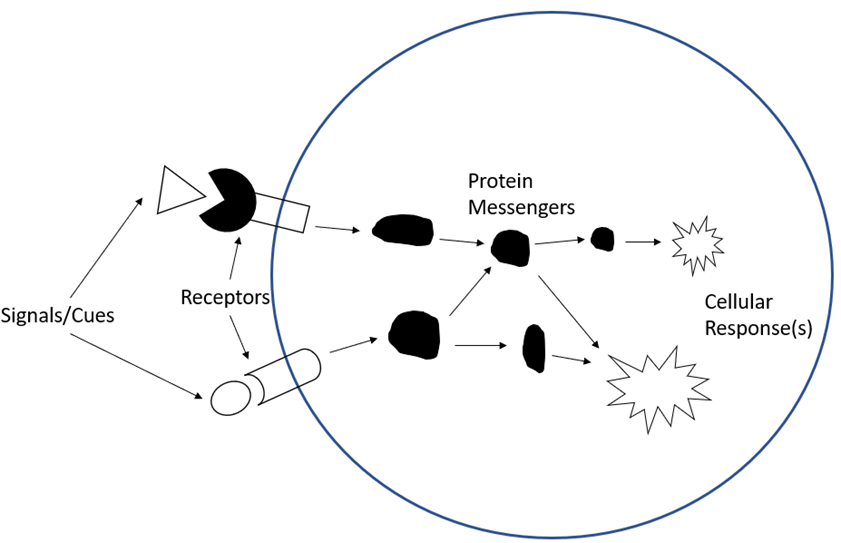

The notochord is formed at a time in development when unspecialized cells become designated for certain tissue types, such as muscle, brain, and heart. This process involves tightly regulated gene expression, which is coordinated through signaling pathways. A signaling pathway involves a receptor on the outside of a cell responding to an environmental stimulus or other cue. The signal is then transmitted through the cell via protein messengers and causes a response, such as a gene being turned “on” or “off”. Furthermore, different pathways can be interconnected, forming networks.

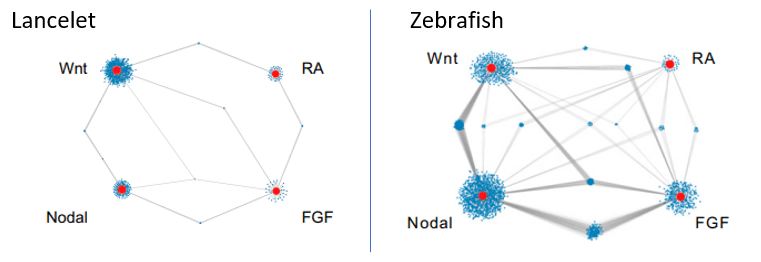

Key signaling pathways are important for developing specific tissues out of unspecialized cells. By manipulating these pathways during development, scientists can study how changes in these networks contributed to vertebrate evolution. To this end, in a recent study published in PNAS, scientists perturbed these key signaling pathways in lancelet and zebrafish embryos as cells gained specialized functions and compared what happened to gene expression and gene regulation. The researchers found multiple genes that responded to changes in these signaling pathways in zebrafish, but not in lancelets. In zebrafish, these genes responded to changes in multiple pathways, rather than just one, suggesting that these pathways are more interconnected in vertebrates.

Vertebrates have types of cells not seen in invertebrates. The increase in interconnection of signaling pathways in vertebrates most likely allowed for tighter regulation of gene expression and a subsequent increase in tissue complexity over evolutionary time. So, while lancelets may look unassuming burrowed in the sand, these hard to spot invertebrates have been instrumental in our understanding of how vertebrates evolved, and why interwoven gene regulation was important for our evolution.

Edited by Anna Rogers

Leave a comment