Researchers test gene therapy to reverse the characteristics of a rare, vision-loss causing eye disease

Eyes allow people to do things like drive to work, read the newspaper, and watch television. But have you ever thought about how eyes are able to see? Well, in the back of each eye there is a thin layer of tissue called the retina. Retinas convert the light that they sense into signals that are read as images by the brain. Unfortunately, however, there are a number of retinal diseases and conditions that cause early- or late-stage vision loss.

While there have been some breakthroughs in vision restoration research using animal models such as mice, they may not accurately describe what happens in humans. Stem cells, cells that can generate lots of different cell types, have gained momentum in biomedical research. This is because they can be derived from humans and therefore allow us to directly study human development and disease. Initial human stem cell research involved the use of embryonic stem cells (ESCs) that are obtained from early human embryos, resulting in their destruction. Even though ESCs were often left over from embryos that would have otherwise been discarded after a successful implantation, the public voiced ethical concerns regarding their use in research. This issue has since been resolved with the discovery of induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs), where cells from human tissue can be collected in a non-invasive way and then reprogrammed to a state where they can become many different cell types (e.g., retinal cells, liver cells, brain cells, etc.). Most notably, iPSCs can be derived from patient cells, giving a theoretically unlimited supply of sample to study the disease and understand how it develops, what genes are involved, and what drugs or therapies could be beneficial. iPSCs can also be helpful to test strategies like gene therapy before implementing them into patient care. Gene therapy involves editing a gene in patient cells and seeing if that reverses or diminishes the characteristics of a particular disease.

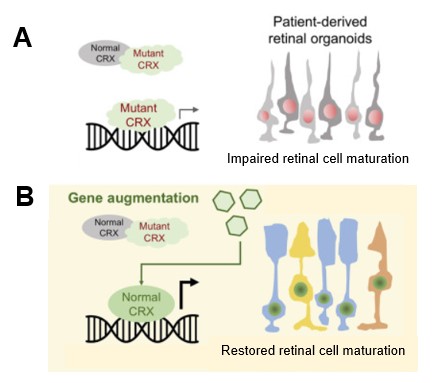

In a recent study published in Stem Cell Reports, researchers used iPSCs to study Leber congenital amaurosis (LCA), a rare eye disease that causes children to lose their vision at a very young age. Children with LCA have severely underdeveloped retinas that do not function properly. LCA can be caused by mutations in the gene coding for the CRX protein, a protein that is important for development of the retina. This mutation leads to less CRX protein being made, which is detrimental to the retina. Currently, there are no treatments that can fully restore sight to LCA patients. The purpose of their study was to test the effectiveness of CRX gene therapy, which would hopefully restore levels of CRX protein in the retina, on rescuing the effects seen with LCA.

The authors derived iPSC cells by reprogramming skin cells taken from CRX-mutant LCA patient skin biopsies. These iPSCs were then differentiated, or transformed, into retinal organoids, 3-dimensional masses of tissue resembling retinal tissue, and studied. Retinal cells of the diseased tissue failed to mature properly (Fig. 1A), but when a non-mutated form of the CRX gene was introduced back into these diseased retinal organoids (Fig 1B), the authors saw promising results: the CRX protein increased to normal levels and so the retinal cells were able to mature and develop almost completely normally. In addition, the restoration was long-lasting, with no sign of decline for at least 6 months post-treatment.

The ability of CRX gene therapy to restore healthy retinal cells to diseased and underdeveloped tissue offers a glimmer of hope surrounding the treatment of rare forms of eye disease. In addition, iPSCs provide researchers with a way to study human development and disease safely and humanely in a way that was impossible to do not even 20 years ago. Hopefully, continued research in this area will lead to the development of more effective therapies that could reverse vision loss.

Edited by Maura McDonagh

Leave a comment