For more than a century, scientists said one thing with certainty: mice do not menstruate. A new study has now rewritten that rule, and with it, how we study one of the most common biological processes on Earth.

For nearly half of the human population, menstruation is a familiar rhythm. Every month, tissue builds up inside the uterus, breaks down, leaves the body, then heals and starts again. This cycle repeats for years, often decades, without leaving scars. Despite how common this process is, science has struggled to study it as a whole.

One reason comes down to a small but important detail: mice, the most widely used animals in biomedical research, don’t menstruate. Their hormones rise and fall, they ovulate, and their uterine lining thickens, but when hormone levels drop, they don’t shed that tissue. Instead, when hormone levels fall, the uterine lining is resorbed rather than shed, a hallmark of the rodent estrous cycle rather than menstruation.

That difference has shaped what scientists could study. To understand menstruation, researchers relied on primates or on small samples of human uterine tissue grown in dishes. Those approaches offered glimpses, but never the full sequence of events as they unfold inside a living body. Menstruation happened in pieces, not as a continuous story.

In a new, exciting study* from Dr. Kara McKinley’s lab at Harvard University, researchers wondered whether that limitation was truly unavoidable. Rather than force mice to menstruate, they asked whether it was possible to guide the uterus through biological steps parallel to the monthly human experience.

The result is a system they call X-Mens, short for experimentally induced menstruation. X-Mens doesn’t turn mice into human stand-ins, but it does give researchers a way to trigger menstrual-like bleeding in a controlled and repeatable way.

The idea is surprisingly straightforward. The team engineered mice so that specific uterine cells carry genetic switches that remain inactive under normal conditions. These switches can be flipped on at precise moments, allowing researchers to mimic the hormonal signals that trigger menstruation in humans.

Activation is achieved using tamoxifen, a drug commonly used in mouse genetics to control inducible systems. When administered at the right time, it initiates a cascade of signals similar to those that occur when progesterone levels fall at the end of the human menstrual cycle. The uterine lining responds by breaking down, shedding, and then beginning the process of repair.

Given the long-standing assumption that mice cannot menstruate, one might expect the first instance to be met with surprise. Instead, it served as confirmation that the system was working exactly as designed. For the first time, researchers could watch the entire process unfold, from start to finish, in a living organism. That control made it possible to ask a deeper question: what is the uterus actually doing during menstruation?

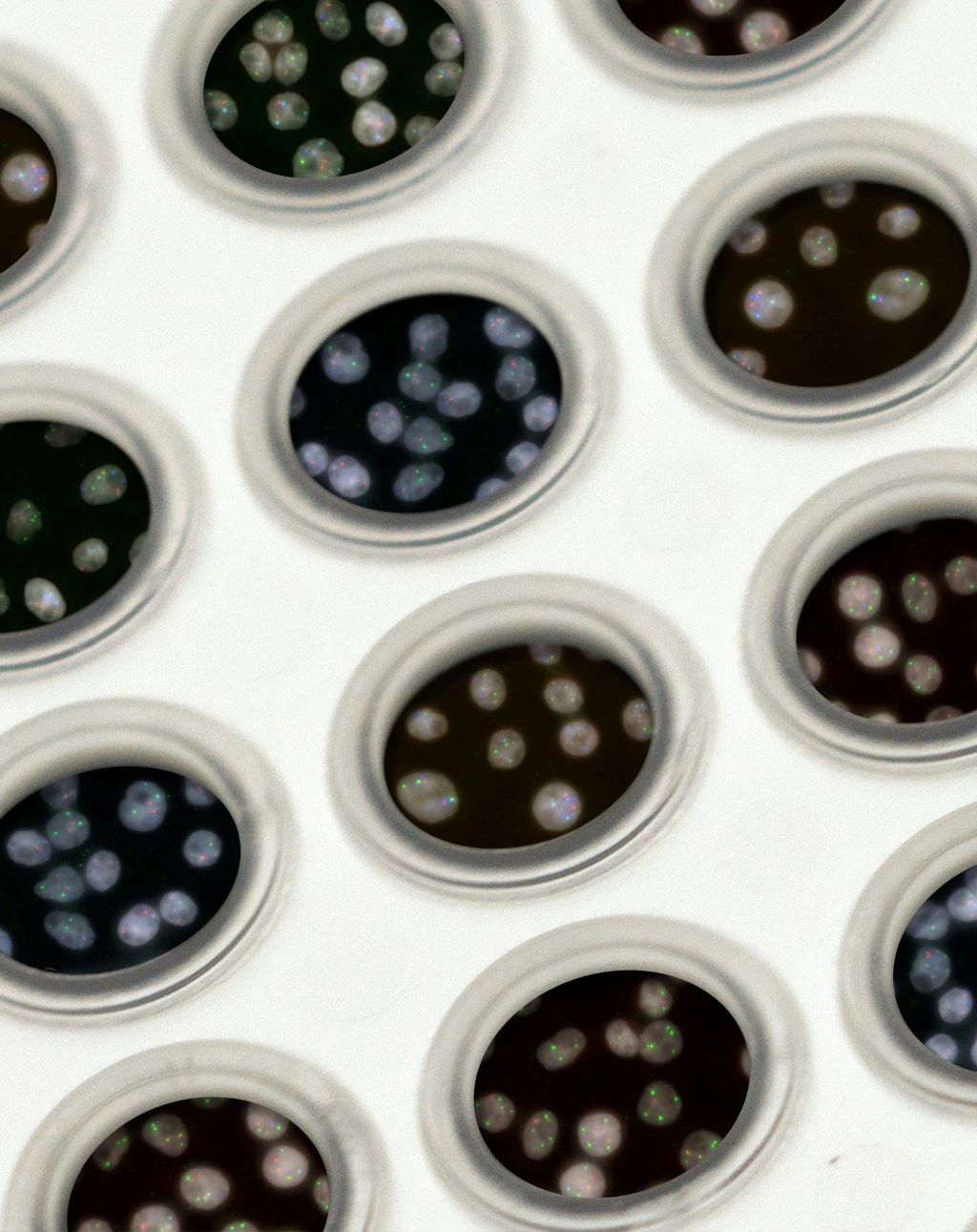

To find out, the researchers tracked which genes were active in different mouse uterine cells over time. Instead of seeing a simple divide of old tissue on top and new tissue underneath, they found something more dynamic. Cells organized themselves into ring-like patterns, similar to ripples spreading across water.

Each ring reflected a distinct cellular state. Cells at the center were actively breaking down tissue, while surrounding rings contained cells transitioning toward repair and regeneration. Destruction and rebuilding were not separate phases occurring one after the other. They unfolded side by side, coordinated in space and time.

This matters because menstruation has long posed a biological puzzle. Most tissues scar when they are damaged. The uterus does not. Month after month, it breaks down and rebuilds itself with remarkable precision. Seeing this process unfold in overlapping waves offers a potential explanation for how that scar-free healing is achieved.

The model also opens the door to questions that have lingered for decades. Why does this process usually heal so smoothly? What happens when the timing is disrupted? Why do some people experience chronic pain, heavy bleeding, infertility, or pregnancy loss?

These questions are not new, but the tools to answer them have been limited. By providing a living, repeatable system in which the full menstrual-like cycle can be observed as it unfolds, X-Mens allows researchers to test how disruptions in signaling, timing, or repair may lead to disease.

Menstruation has long sat at the margins of biomedical research, shaped not only by technical challenges but also by cultural discomfort. It is a routine human experience that has rarely been treated as a central biological process worthy of sustained attention.

X-Mens does not solve women’s health, but it changes what can be seen. By turning a process once inferred indirectly into one that can be observed in real time, it offers a way to ask deeper questions about how the uterus heals, and what happens when that precision breaks down. A biological cycle experienced by nearly half the population is no longer hidden behind technical barriers. And with that visibility comes the possibility of understanding it, at last, on its own terms.

*This study was posted on bioRxiv, a preprint server, and has not yet undergone peer review.

Edited by Zach Patterson and Jameson Blount

Leave a comment