It’s time to dig a little deeper into some newer genetics concepts. Previously in this series, we have explored the ins and outs of cell division and other genetic processes as a way to dive deeper into society’s ills and find ways to use our scientific knowledge for the betterment of these issues.

Today, we’re tackling another concept from the curriculum: epigenetics.

If you’re like me, you probably learned in school that DNA is a fixed blueprint. You get what you get, and that’s the end of the story. But the discovery of the epigenome has radically changed that.

Think of your DNA as a vast musical score. The notes (your genes) are fixed. But the epigenome provides the “director’s notes”, the way that the music is played, like writing staccato, crescendo, or tacit (silence) over certain passages. It’s a system of chemical tags that sit on top of the genome and act like on/off switches or volume dials for your genes.

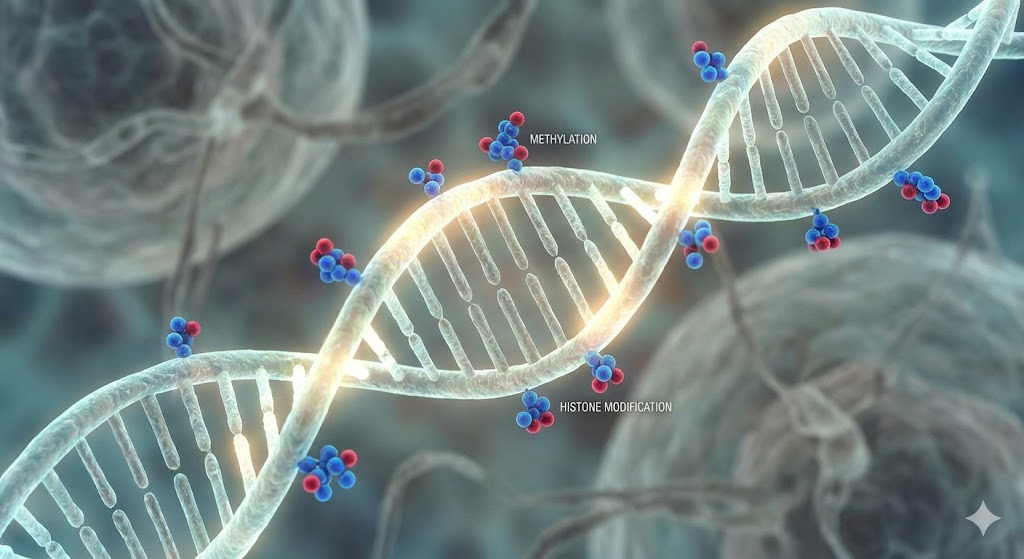

The two primary tags are methylation (which often silences genes, when it occurs around their starting points) and histone modifications (which can loosen or tighten the DNA “spool” to make genes active or inactive). These are not static, but dynamic, and can be influenced by a person’s environment, which includes diet, exposure to toxins, and, critically, exposure to stress and trauma.

This phenomenon provides a tangible, biological mechanism linking our lived experiences to our genetic expression. And as a society, we are only beginning to grapple with what that means.

The Story: Trauma’s Three-Generation Echo

For decades, in many different human services communities (healthcare, education, etc.), we’ve talked about intergenerational trauma, or the notion that certain sociological factors appear to be passed down through an inheritance pattern. Despite this, the question has always lingered: is it “nature” or “nurture?” Is trauma passed down biologically, or are the impacts of trauma felt as a result of being raised by parents suffering from severe, untreated PTSD?

A groundbreaking study published in 2025 offers additional clarity on this important issue. The study focused on families affected by the 1982 Hama massacre, a brutal, month-long siege in Syria that left tens of thousands of civilians dead.

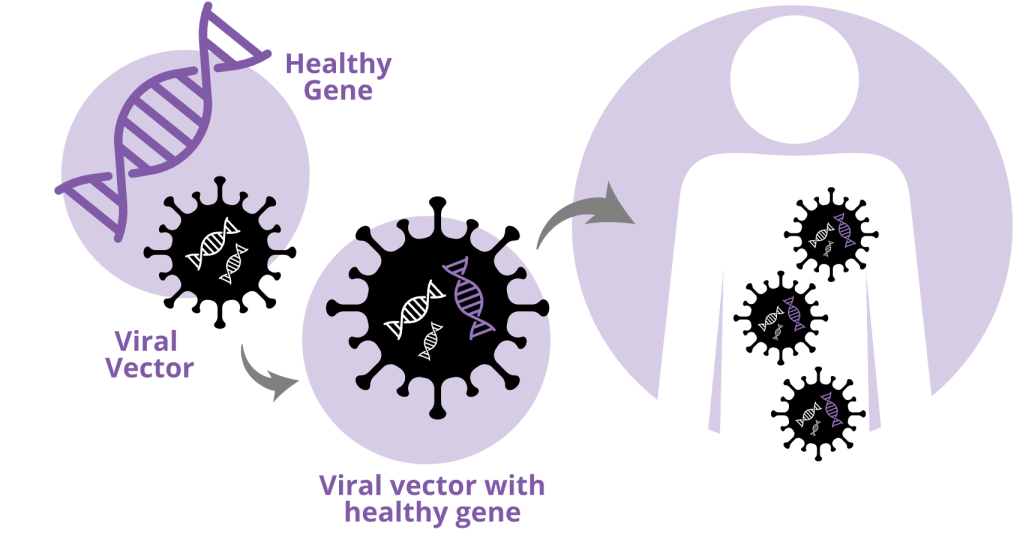

The researchers, in a unique collaboration co-led by Jordanian molecular biologist Dr. Rana Dajani, designed a study to isolate the biological “signature” of this specific trauma across three generations as follows:

- G1: Grandmothers who were pregnant during the 1982 Hama massacre

- G2: Their children, who were exposed in utero

- G3: The grandchildren, who were never themselves exposed to the 1982 violence

The findings are staggering. Researchers identified distinct epigenetic signatures for each group, primarily in the form of DNA methylation, which is the most common chemical tags that attach to the DNA and regulate how genes are turned on or off.

The G1 women who directly experienced the violence showed unique epigenetic marks at 21 locations linked to their exposure. These marks were found on genes involved in critical biological functions, such as cell survival and communication.

The G2 children, exposed in the womb, showed signs of accelerated epigenetic aging due to the same 21 epigenetic marks in their mothers. In other words, their biological clocks were “older” than their chronological age because they had these trauma markers from their birth. This suggests that the trauma of the massacre shifted their cellular development during embryonic development, potentially increasing their risk for age-related diseases later in life.

But the most profound discovery came from the G3 grandchildren. This generation, with no direct experience of the massacre, carried 14 of the original 21 epigenetic marks that their grandmothers had. These markers suggest that the body’s chemical response to violence was preserved and passed down through the oocytes (eggs) of the G2 generation even before the grandchildren were conceived. Interestingly, most of these markers across all generations showed the same “directionality,” meaning the grandchildren’s DNA was reacting to the trauma in the same way their grandmothers’ did.

This is the first strong human evidence for a phenomenon previously only seen in animal models: the genetic transmission of stress across multiple subsequent generations. The echo of that 1982 trauma was physically present in the genomes of children born decades later.

The Social Justice Link: From Blame to Biology

This is where the science lesson collides with our society. We often judge people for being different, for “acting in certain ways,” or for being “stuck in the past.” We see intergenerational cycles of poverty or abuse and, in our worst moments, default to a narrative of blame, using coded language like “culture of poverty”. We have a portfolio of myths about trauma, chief among them that sufferers should just “move on”.

This is especially true for refugees. The very word “refugee” is often equated with a stigma , and this stigma is a major barrier that prevents people from seeking help for the very real help and support they need.

The Hama study, and the field of epigenetics, offers a powerful counternarrative. It provides a physical mechanism that refutes the blame game. Systemic injustices like racism, poverty , and violence are not abstract sociological concepts; they are chronic stressors that can leave tangible, molecular marks on our biology.

When we see a person trapped in a cycle of trauma, we are not witnessing a moral or cultural failure. We may be witnessing the embedded, biological echo of a past catastrophe.

Integrating these insights into our biological curriculum could profoundly influence how future generations grapple with complex social issues. If students truly grasp the mechanisms of epigenetics, understanding how environments shape gene expression, we may see a shift in how society approaches systemic racism, the displacement of refugees, and the treatment of marginalized groups. The question remains: Can we, as a society, create the conditions necessary to better understand and support trauma-affected individuals? As an educator, social worker, doctor, could we better do our jobs to help someone impacted by trauma? Or will our societal norms and intolerances continue to impede physiological and social progress?

This highlights the critical ‘humanity piece’ of scientific literacy. Epigenetics is not merely a scientific novelty; it is a mirror reflecting our collective impact. Scientific knowledge is inert if we fail to comprehend its implications for human welfare. We can do better, and that evolution begins with how we teach and learn about science.

The Point: Beyond “Damaged Goods”

This new knowledge is a powerful tool, but it is also a dangerous one. We must fiercely resist the urge to replace genetic determinism (the idea that genetics alone determine someone’s fate) with a new “epigenetic determinism”. This research cannot become a sophisticated, 21st-century version of “bad blood”—a new scientific-sounding way to label people as biologically damaged or broken, which would only reinforce stigma.

The potential antidote to this danger comes from the Hama study itself.

Dr. Rana Dajani, the study’s co-lead and herself a grandchild of a woman who survived the Hama attack, explicitly challenges the Western idea of victimhood, or the idea that trauma is individual and does not get transmitted to future generations. She points out that the 14 inherited epigenetic sites found in the G3 grandchildren were not associated with any known disease pathways.

This led her to a profound hypothesis. What if it’s not damage at all? What if it’s an adaptation?

She calls this concept “my grandmother’s wisdom“. These inherited marks might be an evolutionary warning; a biological preparation passed down to help future generations adapt to difficult environments. This single idea brilliantly reframes the narrative from one of victimhood to one of agency and adaptability.

This is the fulsome understanding we need. This science provides a biological basis for trauma-informed medical/educational practice , which urges us to reframe trauma responses not as personal failings, but as physiological reactions to extreme stress that are intergenerational, and adaptive mechanisms for those that we work with. They are not personal failings.

The Hama study doesn’t just teach us about epigenetics. It gives us a biological mandate for empathy. It proves that our social and political actions—our wars, our prejudices, our systems of injustice—have consequences that are written into our very biology. As the researchers concluded, this knowledge should help people be more empathetic and should underscore the importance of violence prevention.

Epigenetics shows us that we can adapt from the traumas imposed by our circumstances. Let’s use the echo of trauma to grow our collective empathy.

Edited By: Olivia Fish, Amanda N. Weiss

Leave a comment