While there are no drugs to treat Duchenne muscular dystrophy, there is still hope for a treatment that can alleviate its cause and symptoms. A new gene therapy approach that introduces a mini version of the dystrophin gene may be a new option to treating this genetic condition.

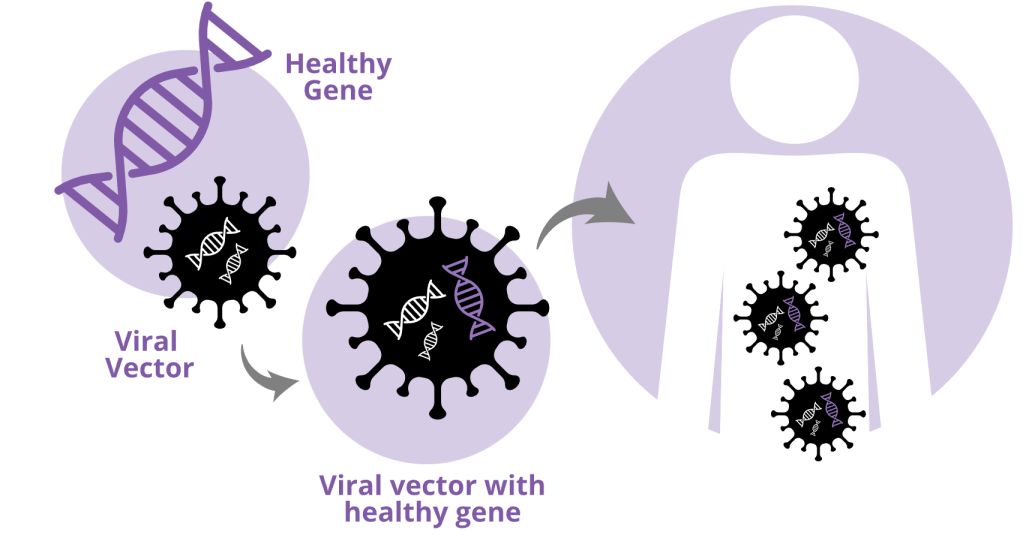

Image courtesy of https://www.askbio.com/aav-gene-therapy/

When something in your house breaks, you have two options: fix it or replace it. The same principle can be applied to the human genome when gene mutations occur. In some cases, the gene mutation can be easily fixed by swapping out the incorrect base pair for the correct one. This is similar to simply replacing the hinge on a creaky door. This tactic was recently used to treat sickle cell disease. However, in scenarios where a doorknob is missing or the door itself has holes in it, fixing just a faulty hinge won’t resolve the issue. Instead, an entirely new door is needed.

A genetic disease that can benefit from this replacement approach is Duchenne muscular dystrophy (DMD). The disease is caused by various recessive mutations in the dystrophin gene, which is located on the X chromosome. This means that the disease is X-linked and requires the presence of one mutated chromosome, for individuals that are XY, and two mutated chromosomes for individuals that are XX. Due to its X-linked nature, this disease is relatively rare and generally occurs in individuals assigned male at birth. The dystrophin gene produces a protein that helps stabilize and protect muscle cells; thus, mutations in this gene cause muscle cells to atrophy and eventually die. Individuals with DMD typically lose the ability to walk between the ages of 9 and 14, and as the disease progresses, they experience heart and lung failure, which ultimately lead to death.

DMD causes loss of function in the dystrophin gene, and due to the numerous mutations that result in this loss of function, the best option is to replace the gene. This can be achieved either by activating an alternative copy of the gene, as in the case of sickle cell and beta-thalassemia, or by introducing a corrected version of the gene through various gene delivery methods. These precision delivery methods have been successful in mitigating other neuromuscular diseases like spinal muscular atrophy (SMA).

Since no alternative version of the dystrophin gene exists, researchers in this study opted to try and replace the mutated DMD gene instead. Unfortunately, the dystrophin gene is too large to be used in any of the current gene delivery methods. Thus, the authors created the micro-dystrophin gene, which contains all the necessary elements for the dystrophin protein to perform its functions but drastically reduces its size so that it can be delivered effectively.

Another hurdle in this therapy is ensuring that the micro-dystrophin protein is only expressed in the areas of the body that need dystrophin, specifically in areas with muscle cells. To overcome this problem, the authors placed the micro-dystrophin gene under the control of a gene promoter and enhancer that are optimized to express genes in the muscles, diaphragm, and heart. This means that while the gene can theoretically be expressed in any cell it enters, there is a strong preference for the micro-dystrophin to be highly expressed in muscle cells.

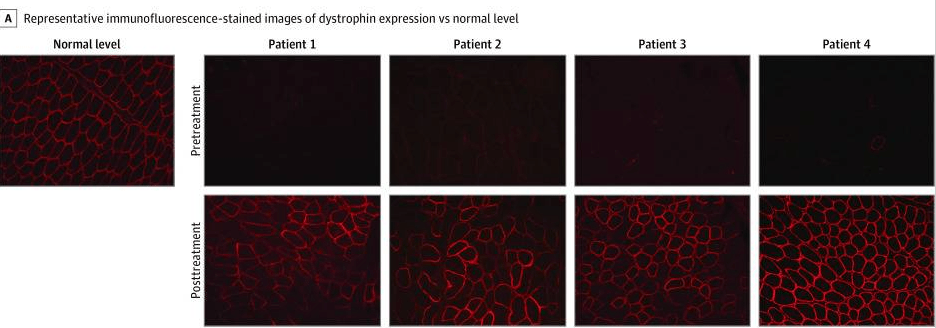

To confirm that the micro-dystrophin gene was both delivered and expressed in muscle cells, the authors performed immunohistochemistry, or protein staining, of the muscle tissues from the individuals both before and after the therapy was administered (figure below). They found that after the therapy was given, there was a drastic increase in the expression of dystrophin (red stain) in the muscle cells of the individuals, and these expression levels nearly matched those of a person without DMD.

Figure 3 from Mendell et al. licensed under Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Immunofluorescence staining of gastric muscle before and after treatment with the gene therapy. Red staining shows presence of the dystrophin protein.

While the expression of dystrophin was increased by the gene therapy, the authors also looked at the functional impact of this enhanced expression by utilizing the North Star Ambulatory Assessment (NSAA).This is a physical assessment that includes activities such as standing up from a sitting position, jumping, and running. The individuals were initially scored before administration of the therapy and again a year after the single dose. The authors found that all individuals had an improved score. This was complemented by data that showed, at the molecular level, there was a decrease in muscle damage.

Since the publication of this article in 2020, a gene therapy using this micro-dystrophin gene has been approved by the United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA). Elevidys was approved for the treatment of Duchenne muscular dystrophy in 2023. This approval was achieved upon additional clinical trials and larger sample sizes of individuals treated with the therapy.

While not as simple as replacing a door in your house, the same principle applies to this kind of gene therapy used to treat Duchenne muscular dystrophy. As our understanding of genetic conditions grows and our ability to address the underlying mutations becomes more effective, we may be able to replace much more than genetic doors in the future. This work is just one example of how the scientific community is expanding our toolbox for treating genetic diseases.

Edited by Sadia Bhatti and Jameson Blount

Leave a comment