Stories bring people together, help learners see deeper meaning, and provide much needed context to learning. Here we examine the different sides of the home genetic revolution, and how something that seems exciting, has many potential societal and ethical drawbacks to it. Its important to be informed of these stories, so we can make good scientific decisions in our everyday life.

Stories bring people together, help learners see deeper meaning, and provide much‑needed context to learning. In our genetics unit we have been looking at how DNA is copied in every dividing cell and how sequencing technologies let us read that information. Today I invite you to step into my classroom and consider what happens when a simple vial of saliva becomes the gateway to a complex web of personal, societal and ethical questions.

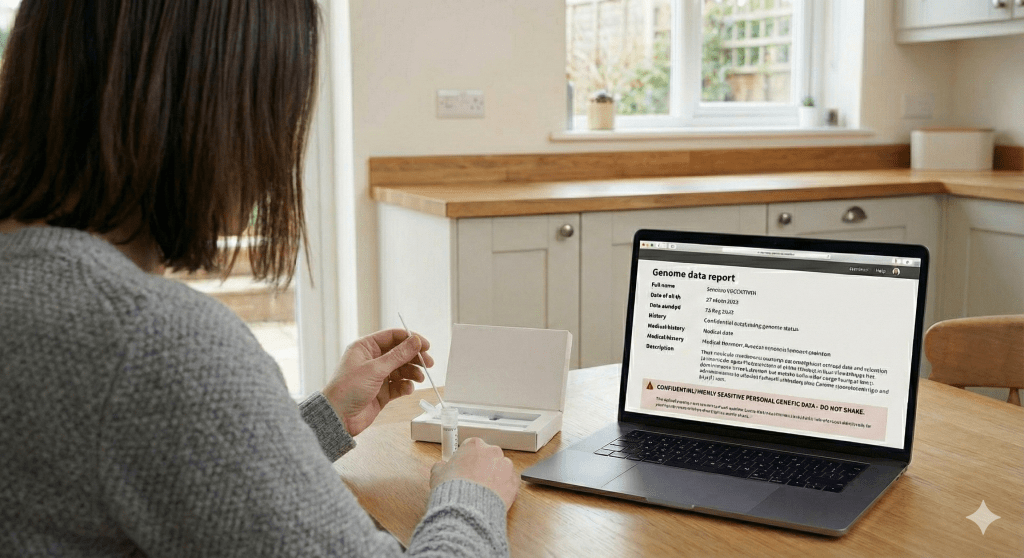

A few years ago a revolution in personal genomics began. Companies promised that, for a few hundred dollars, you could spit into a tube, mail it off, and in a matter of weeks unlock the secrets of your DNA. Among the first of these was 23andMe, founded in 2006 by a group of Silicon Valley entrepreneurs who wanted to democratize access to genetic information. The company quickly became synonymous with home DNA testing. People discovered their ancestry, connected with long‑lost relatives and learned about traits they never knew they carried. For many, 23andMe made genetics accessible and fun.

But the story took an unexpected turn. In March 2025, the company sought Chapter 11 protection and arranged to sell its assets to a new non‑profit, TTAM Research Institute, founded by its former CEO. A federal bankruptcy court approved the sale and TTAM agreed to buy 23andMe’s personal genome services and telehealth business for about $305 million. The sale was controversial because it involved transferring the genetic data of roughly 15 million customers to a new owner. Privacy advocates and state attorneys general argued that consumer DNA data might be used or disclosed without proper consent. By July 2025, only about two million customers had requested that their samples be destroyed. Meanwhile, regulators were still addressing a 2023 breach in which hackers accessed sensitive information from seven million 23andMe users. UK authorities fined the company millions for security failures and criticised its slow response to the incident. Members of the U.S. Congress questioned whether the genetic data trove could end up in the hands of foreign adversaries. Overnight, a company that once symbolised empowerment became a lesson in how quickly trust can erode when technology outpaces regulation.

Why this matters to us

In biology classrooms, a common learning outcome involves having students explain how scientific research and technological development help achieve a sustainable society (See Alberta Program of Studies). This is tied to assessing the impact and value of DNA sequencing on the study of genetic relationships. It is easy to show students the wonders of sequencing: mapping genomes, tracing ancestry and diagnosing disease. But to develop scientific literacy we must also explore the messy side of science, the social contexts, ethical dilemmas and potential misuse of technology. The story of 23andMe is a perfect case study.

Questions to ponder

As you read about 23andMe’s rise and fall, I would invite my students to consider these questions:

- What happens to your genetic data once you mail that saliva sample? In the bankruptcy sale, 23andMe’s data trove was treated like any other asset, subject to transfer to another organisation. Do you find that troubling?

- Who analyses the data, and under what oversight? The US Food and Drug Administration once ordered 23andMe to halt its health reports because they were not sufficiently validated, allowing only ancestry results until the company could prove reliability.

- Can your data be sold or shared? The attorneys general lawsuit warns that, without explicit consent, customer data might be disclosed to third parties. 23andMe has long shared de‑identified data with research partners, and privacy rules are still evolving.

- What happens if the results are wrong? In the early days, health risk reports were suspended because the company lacked evidence of accuracy. Imagine receiving a report stating you have a high risk of an early‑onset cancer – would you change your life plans? What if that report is later shown to be inaccurate? Would you have spent your savings on a last‑minute world tour or launched a fundraiser for treatment you never needed?

When I pose these questions in class, students typically fall into three camps. Some adopt a “YOLO” (you only live once) mentality, deciding to live it up; others become paralysed by fear; and some carry on as usual. Each choice has consequences – emotional, financial and relational. And if the test is wrong, each path leads to regret or awkwardness.

The worst‑case scenario

Thinking about worst‑case scenarios is not meant to scare you away from science. Instead, it pushes you to interrogate the promises of new technologies. In my classroom we call this the I Am Legend postulation: what if the cool technology goes horribly wrong? Beyond personal decisions, misuse of DNA data raises concerns about genetic discrimination, privacy infringements, and even national security. When 23andMe’s data trove became a bargaining chip in bankruptcy, some members of Congress worried that foreign governments might access Americans’ genetic blueprints. The 2023 data breach reminded us that sensitive information, once exposed, cannot be changed like a credit‑card number.

Toward scientific literacy

Stories like these show that scientific literacy is more than memorising facts or conducting lab experiments. It requires the ability to evaluate technology’s benefits and risks, to understand how regulation and corporate decisions affect society, and to recognise when enthusiasm overshadows caution. The Nature of Science (NoS) is the idea that science is a human endeavour shaped by history, culture and politics – reminds us that discoveries do not occur in a vacuum. The 23andMe saga teaches us that informed consent, data privacy and social justice are as much a part of genetics as base pairs and chromosomes.

So before you do a spit take, decide whether you are comfortable with all the implications of giving your DNA away. 23andMe’s bankruptcy is a cautionary tale about what happens when commercial enthusiasm meets inadequate oversight: millions of people willingly shared their most personal data, and only later did many of them realise what they had surrendered. As citizens and scientists, it is our civic duty to scrutinise new technologies with curiosity and scepticism. Let’s hope we can evaluate all future innovations this thoughtfully.

Class dismissed.

Edited by JP Flores, Jameson Blount

Leave a comment