Sexual reproduction offers many evolutionary advantages. However, in some cases, female asexual reproduction reigns supreme. Yahshiro et al. explore how and why queens overthrew kings in certain termite colonies.

The Greek mythological community of the Amazons is what most people picture when imagining a society made up entirely of women. While the Amazons were a female-only society, they still relied on interactions with males for reproduction. What might come as a surprise is that populations like the Amazons exist not just in myth, but also in real life. In fact, real all-female communities in nature seem even more mythological than the myth themselves, as they have completely forgone the need for males for reproduction.

Before Yahshiro et al.’s study, the occurrence of asexual insect communities – communities that do not rely on sexual reproduction – was only seen in some ant and honeybee species. However, these communities do not rely solely on asexual reproduction to generate their offspring. In these communities, male members are produced from asexual reproduction and female members are produced by sexual reproduction. In Yahshiro et al.’s study, the authors report the first ever occurrence of completely female termite colonies in the coastal regions of Japan. With the absence of males in these communities, reproduction must occur asexually. Asexual reproduction occurs when an unfertilized egg is able to give rise to viable offspring. This type of reproduction is oftentimes associated with yeast and plants rather than animals.

Asexual reproduction in the animal kingdom is rare due to the plethora of benefits that arise from sexual reproduction including a diversification of the gene pool. As mentioned above, even in species that are reported to reproduce asexually, such as ants and honeybees, these species often use a combination of sexual and asexual reproduction due to how chromosomal sex is assigned to offspring. In these species, females are diploid – having two copies of each chromosome – and are produced by sexual reproduction. Males, on the other hand, are haploid – having one copy of each chromosome – and are produced by asexual reproduction. Thus, it’s extremely rare to find species that reproduce solely by asexual reproduction. However, they do exist, indicating that there are evolutionary benefits to communities that reproduce asexually.

This study began when the authors identified colonies of termites in coastal regions of Japan that appeared to be solely female. This was interesting as colonies of the same species are also found in other areas of Japan, but these colonies contain both males and females. To determine the sexes of the termites in these colonies, the researchers used a combination of physical markers of sex and looking at the sex chromosomes. In the suspected female-only colonies, all the termites had female markings, and their sexes were confirmed by the presence of female sex chromosomes. However, the researchers were concerned that these colonies had males, but they simply hadn’t been able to locate them. To further prove that these were all-female colonies, the researchers looked at the storage of sperm in the queen termites. Long term sperm storage is a common phenomenon in insects like honeybees and ants due to the relatively short lifespans of fertile males compared to fertile females in these species. The logic behind this experiment was that if hidden males were present in the colonies, the researchers should be able to find sperm stored in the queens. In the sexually reproducing, mixed sex colonies of the Japanese termites, they found that the queens all had sperm in these storage areas of their bodies, but the queens of the female-only colonies had no sperm in these areas. From this information, they concluded that the female-only colonies were reproducing asexually.

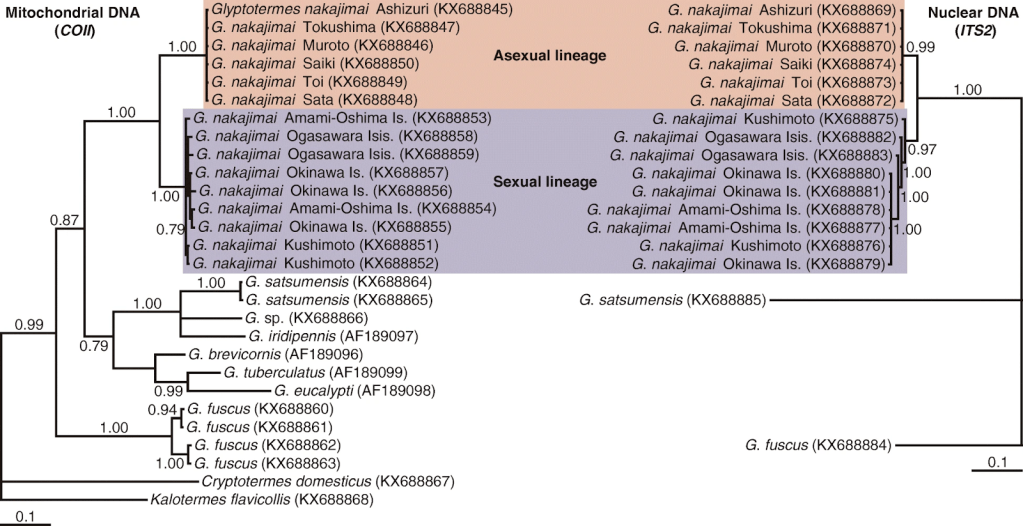

Next, the authors explored the evolutionary relationship between the sexually reproducing colonies and the asexually reproducing colonies. They wished to determine when the two colony types diverged from each other. To do so, they created a phylogeny – a tree of relatedness – based on two gene markers in termites. They found that these two markers were able to differentiate the asexual and sexual colonies such that asexual colonies clustered in one branch and sexual colonies clustered in a separate branch (see figure below). They note that because all other termites in this particular genus of termites reproduce sexually, their results demonstrate a single origin event of asexual reproduction within this species, meaning that all the existing asexual colonies arose from a single population of termites that split off from the sexually reproducing populations. This is evidenced by the fact that there is a single common ancestor linking the sexual and asexual lineages in the phylogenetic tree. They estimated that the divergence of these sexual and asexual lineages was about 14 million years ago but caution that sampling of other sexually reproducing colonies are needed in order to confirm this.

Figure 4 from Yahshiro et al., licensed under Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. This pair of phylogenetic trees shows the clustering of asexual and sexual termite lineages, indicating that the two lineages are genetically distinct and diverged from a common ancestor.

While it’s impossible to prove exactly why asexual reproduction evolved in these coastal termite colonies in the first place, the authors provide several scientific theories as to why asexual reproduction was evolutionarily favorable. One trait the authors note as evolutionarily advantageous is that the asexual, female-only colonies are often founded by at least two queen termites. This is opposed to the founding of sexually reproducing colonies by one king and one queen. Having multiple queens found a colony increases the chances of the colony surviving by allowing for the death of one or more queens. Another benefit is that these colonies can allow for more effective defense against invaders by making all the soldiers look the same. The authors found that in the asexually reproducing colonies, soldiers had a more uniform head size compared to the sexually reproducing colonies, which allowed them to more efficiently defend the colony and promote colony survival. Additionally, the authors found that the asexually reproducing colonies had a fewer number of soldiers than sexually reproducing colonies. From this, they hypothesized that the asexually reproducing colonies could divert energy from caring for these soldiers to investment in other areas of the colony. Overall, these aspects might allow for a higher survival of the female-only, asexually reproducing colonies.

Termites are far removed from the mythical Amazons, but they share commonalities in their strong female soldiers and male-free societies. The research done in this study presents a more extreme version of the Amazons, but one that exists in reality. While asexual reproduction is relatively rare in the animal kingdom, this work proves that in some cases, it is evolutionarily possible and beneficial, and that species that once had active male participation in reproduction can evolve to utilize solely asexual reproduction, at least in some communities. This work, which is the first to identify that termites can reproduce asexually, opens the door for future work into how asexual reproduction might have evolved in other, yet unknown, members of the animal kingdom.

Edited by Amanda N. Weiss and JP Flores

Leave a comment