Bananas are one of the most consumed fruits globally yet also one of the most wasted. With a shelf life of just 1 week, they may seem to go from perfectly ripe to overripe overnight. In the U.S. alone, an estimated 5 billion bananas are thrown out each year. If you’ve ever hesitated before tossing a mushy banana into the trash, you’re not alone – it’s a small moment that speaks to a much bigger issue of food waste and its environmental impact.

Image from iStock.

In an effort to reduce this food waste, a UK-based agritech company, Tropic Biosciences, has developed a “non-browning” banana using an advanced biotechnology technique, CRISPR-Cas9, to prolong the shelf life of bananas through modifications at the DNA level. We can take a look at relevant research on gene-edited fruit backing up this recent press release, to understand how this can be done. It helps to first distinguish two key processes: ripening and browning.

Ripening is the natural process in which fruit softens and begins to slowly decay. It is induced by the plant hormone ethylene, which leads to a specific and elaborate chain of events called a signaling pathway that turns on genes associated with ripening, as seen in the image below. Ethylene-mediated ripening begins with the ACS and ACO genes which transform ethylene precursors into ethylene (chemical structure displayed in the green rectangle). The newly synthesized ethylene is recognized by receptors that pass signals along until ultimately turning on ripening-associated genes (bottom right of image). In this way, ethylene influences gene function without changing the DNA sequence.

This diagram shows how the plant hormone ethylene triggers fruit ripening by activating ripening-associated genes. This process begins with the ACS and ACO genes; editing these genes can slow the ripening process.

Image from Liu M, Pirrello J, Chervin C, Roustan JP, Bouzayen M. Ethylene Control of Fruit Ripening: Revisiting the Complex Network of Transcriptional Regulation. Plant Physiol. 2015 Dec;169(4):2380-90. doi: 10.1104/pp.15.01361. Epub 2015 Oct 28. PMID: 26511917; PMCID: PMC4677914.

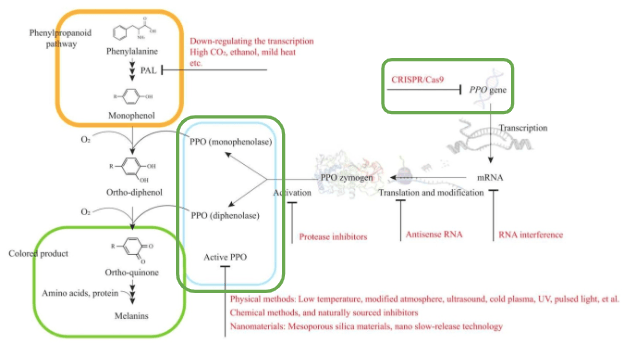

On the other hand, browning occurs when fruit is cut or bruised; for example, when a banana has been peeled. On a microscopic level, the stress of slicing or bruising fruit damages the cell membranes. This induces the chemical process of browning, mediated by the enzyme polyphenol oxidase (PPO) (centermost rectangle in the image below). PPO, produced by the PPO gene (top right in the image below), reacts with phenolic chemicals to produce brown pigments, which appear as brown bruises.

This diagram shows how bananas brown after being cut, due to the activity of the PPO enzyme. Scientists can use CRISPR on the PPO gene to slow this browning process, so bananas stay fresh longer.

Image from Sui X, Meng Z, Dong T, Fan X, Wang Q. Enzymatic browning and polyphenol oxidase control strategies. Curr Opin Biotechnol. 2023 Jun;81:102921. doi: 10.1016/j.copbio.2023.102921. Epub 2023 Mar 23. PMID: 36965297.

Modifying the ACS and ACO genes can alter ethylene-mediated ripening and modifying the PPO gene can alter PPO-mediated browning. By making selective DNA changes, scientists can decrease or inhibit ethylene or PPO function to prolong banana shelf life.

Bananas reproduce asexually through cloning rather than sexual reproduction, like humans. This means every banana plant is genetically identical to the parent — so traditional breeding methods like crossing varieties for improved traits do not work. As a result, there is little genetic diversity in bananas, making them vulnerable to disease and spoilage.

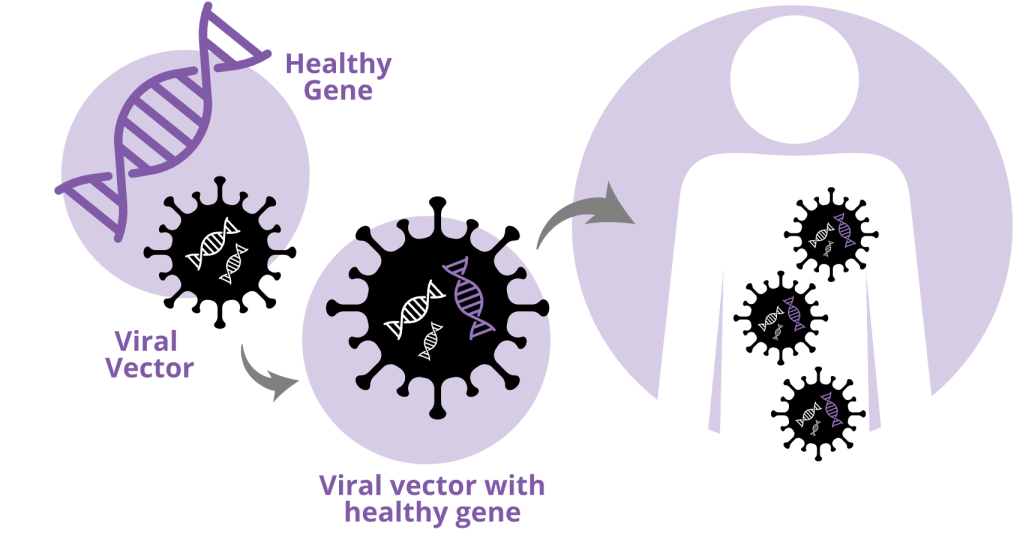

That’s where CRISPR-Cas9 gene editing comes in. With CRISPR, scientists can precisely edit specific genes within the banana’s genome to introduce beneficial traits without inserting foreign DNA. In theory, this is like making changes that could have occurred naturally through mutation, but more specific, intentional, and rapid. To perform CRISPR, scientists target a specific sequence in DNA. Then, the Cas9 enzyme cuts the DNA so that the intended edit can be made. The cell tries to repair this cut, but in doing so, occasionally introduces mutations that can disrupt the gene’s normal function.

In a relevant study from 2021, scientists used CRISPR to edit the ACO gene in bananas to modify ethylene production and select for mutations that would delay ripening. Once a desired gene edit was successfully made, the gene-edited banana plant was propagated clonally so the modified traits would be passed down through generations. Some of the edited banana strains remained green or yellow with no signs of ripening for up to 60 days after harvest. On the other hand, unedited, otherwise “normal”, bananas began to show visible signs of decay after just 21 days. Minor differences were observed in size: only 15% shorter and just up to 14% lighter in weight. Notably, the gene-edited bananas were not significantly different in nutrition. In fact, some gene-edited strains had slightly higher vitamin C contents. Researchers have not determined a definitive reason for this increase, but one possibility is that the extended ripening period allowed for additional accumulation of certain nutrients.

While this study focused on slowing the ripening process, Tropic Biosciences focused on the PPO gene, earning their gene-edited banana the name “non-browning” banana – a banana that, when peeled, or sliced, resists browning for up to 12 hours, extending its usability in fresh-cut produce, food service, and exporting.

A major benefit of CRISPR editing in this context is that no foreign DNA remains in the final product, which means that the bananas are technically non-genetically modified organisms (non-GMO). This distinction eases restrictions on distribution and labeling, and may even lead to broader consumer acceptance.

From the lab bench to the produce aisle, gene-edited bananas represent a sustainable, science-driven solution to global food waste and agricultural vulnerability. This is a great example of how modern genetics can address complex agricultural challenges, reduce environmental threats, and help build a more resilient food system.

Whether or not your next bunch of bananas ripens like clockwork or stays firm for weeks thanks to gene-editing, food waste is a problem that scientists are working to resolve from all angles. Until then, when life gives you browning bananas, make banana bread!

Edited by John Laver and Jameson Blount

Leave a comment