What if the secret to a healthy weight was as simple as taking a nap? For Mediterraneans and their descendants, it might be.

Imagine a young woman named Sophia, who works at her family-owned cafe in her hometown of Athens, Greece. Like many people, Sophia has been trying to get in better shape. When her family takes a break to head home for their afternoon siesta, Sophia goes for a jog. Unfortunately, she doesn’t seem to get the results she is after despite her efforts, and is beginning to question whether all the extra exercise is worth it.

Napping has consistently been linked to negative health markers, such as higher body mass index (BMI), higher body fat percentage, and increased blood pressure — all of which are further linked to obesity and other health problems. In some countries , such as Spain, Italy, and Greece, taking a siesta is part of a normal daily routine. Despite the health risks, people from these areas view siesta as a way to rest and recharge, ultimately boosting productivity. Does this make them more prone to obesity because of their napping habits?

Feeling stuck with her current routine, Sophia starts researching new strategies for weight loss and stumbles upon a recent study which found that taking a siesta, a common Mediterranean custom of a midday nap, affects the success of weight management for those with a certain genetic profile. Curious, she decides to dig deeper into the study.

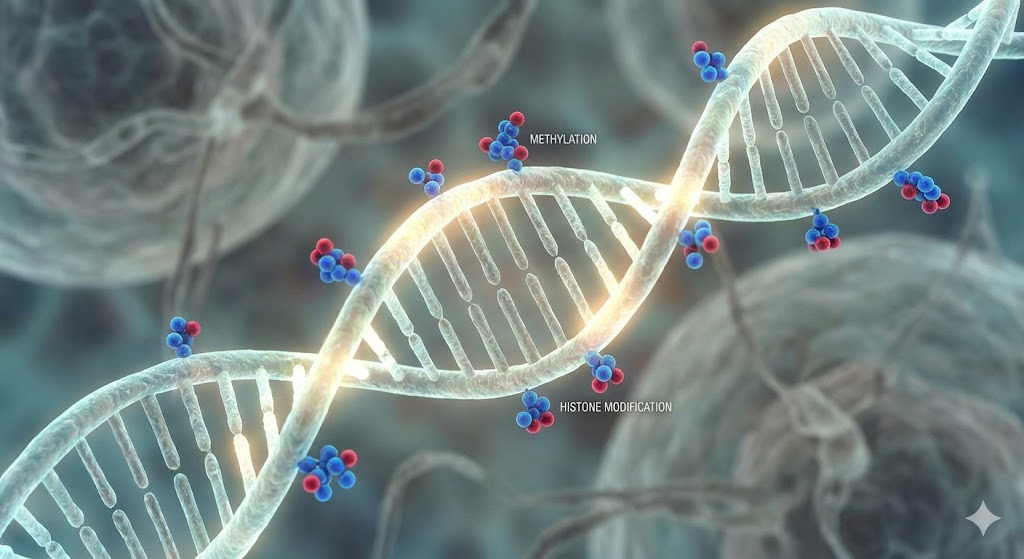

Scientists María Rodríguez-Martín and Diego Salmerón investigated how the genetic profile of Mediterranean people might affect their tendency to nap. They focused on specific changes in participants’ DNA that are associated with napping habits. These small changes in a person’s DNA, known as genetic variants, may alter traits and behaviors, including napping habits.

They analyzed survey responses about sleeping habits from over 400,000 people, alongside their genetic profiles. By comparing the genetic data of individuals with different sleeping habits, they identified 123 genetic variants associated with napping. Many of these variants were found in genes related to circadian rhythms, arousal, and metabolism. For example, variants in the HCRTR1 gene, which regulates the sleep-wake cycle, and the PNOC gene, which influences arousal through eating habits, were found to affect napping traits. By identifying these variants, they could examine how much a person’s genetics may influence their tendency to siesta. However, it is also important to note that this research, based on a specific population and survey data, may be subject to bias.

Sophia’s grandmother, who always takes a nap after lunch, swears by the benefits of siesta. Considering this research, her lack of success with her current routine, and her many family members who incorporate this rest into their daily routines, Sophia considers whether she, too, might benefit from siesta. She decides to take a break from her usual exercise for one week and join her family for siesta instead.

Study participants with more napping genetic variants did take siestas more often than those with fewer napping genetic variants – they had a higher genetic predisposition to siesta. But despite the link between napping and obesity, frequent siestas did not automatically result in higher obesity risk. After classifying participants according to their survey responses and genetics, the scientists monitored their weight over time in response to a weight loss treatment involving exercise and diet, as well as their long-term success in maintaining weight loss or managing a healthy weight. They found that people with a high genetic predisposition to siesta who regularly did so had a lower obesity risk or status compared to those with the same genetics who avoided naps.

By the end of the week, Sophia starts noticing a difference. She feels more rested and energized and even notices she lost a few pounds! Her body seems to be responding positively to the change in her routine.

Just like physical traits – such as eye color – sleeping patterns, such as siesta, are passed down through generations, and thus, tied to our familial and cultural identities. People in Mediterranean cultures who have some combination of the 123 genetic variants linked to napping may be better “protected” from the potential negative effects of napping on weight – so long as they follow the behavior they have been predisposed to. On the other hand, people without these genetic traits, likely from cultures where siesta isn’t common, may find that napping could contribute to weight gain. Likewise, people who do not siesta even though they’re genetically predisposed to do so might struggle. More broadly, if you are genetically predisposed to a certain behavior but actively avoid it, this could have negative impacts on your health – even if that behavior is typically regarded as a negative habit.

In Sophia’s case, her family’s tendency to siesta suggests that she may have inherited variants giving her a high genetic predisposition to siesta. This could explain why she was not seeing progress towards her fitness goals while skipping siesta for an afternoon jog. The extra rest, combined with her genetic predisposition to benefit from siesta, was the right routine to balance her overall health.

This research, and Sophia’s example, emphasize that there isn’t really a one-size-fits-all approach to weight loss, or even overall health. What works for one person may not work for another, especially when you consider individual genetic differences. Ideally, health strategies should be personalized to fit each person’s genetics, environment, and lifestyle.

So, should you start napping to lose weight? Probably not. But it’s worth considering how your family history, cultural practices, and lifestyle may influence your health. Before you swap your gym session for an afternoon nap, remember that personalized health strategies tailored to your unique identity are key to finding what works best for you.

Edited by Ethan Honeycutt and Jameson Blount

Leave a comment