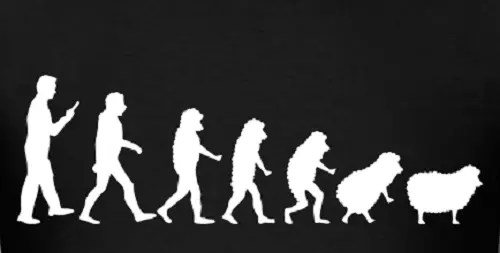

A look into ancient genetics shows how sheep evolved from their wild ancestors and the role that human interaction played in this evolution.

We often consider the Fertile Crescent as the cradle of human civilization. It was here that early humans began to settle down and create cities, invent written language, and invest in agriculture. But oftentimes in history and science, our view is human-centric. We tend to focus on how humans evolved physically, culturally, and linguistically, and forget about the other plants and animals that existed alongside humans during these centuries. Luckily for us, although humans weren’t recording when and where they domesticated certain plants and animals, genetics was.

Just as our genomes tell the story of how Homo sapiens mingled with Neanderthals, the genomes of other organisms also record their evolutionary history. In their study, Daly et al. attempt to translate the genomes of ancient sheep into a tangible history of where and when sheep came into contact with humans and how this relationship ultimately changed the evolutionary fate of modern day sheep.

To answer these questions, Daly et al. sequenced the genomes of over 100 ancient sheep found at different sites across the world within a timeframe of 12,000 years. While the genomes came from many different areas, many of the samples came from the areas in and around the Fertile Crescent. Unlike genetic sequencing today which only requires a swab from the inside of one’s cheek, the DNA used for this study came from sheep bones. However, the sheep genomes themselves don’t reveal anything about what kind of environment these animals lived in. Were these wild sheep or did they live alongside humans and other livestock? To understand the environmental and societal contexts these sheep lived in, the authors formed collaborations with archeologists and anthropologists who were able to examine the sites surrounding the sheep bones and ascertain whether these sheep lived amongst humans by looking for signs of civilization. This information helped to connect the genotype of the sheep with a probable phenotype i.e. whether they were wild, semi-domesticated, or fully domesticated.

Just as human civilization began in the Fertile Crescent, so does the story of the relationship between humans and sheep. While it is known that sheep were domesticated by humans, the exact area within the Fertile Crescent where this domestication process began is unknown. The authors of this study were able to pinpoint the western region of the Fertile Crescent as the birthplace of sheep domestication. They did so by performing a principal component analysis (PCA) of the sequenced genomes. PCA is a technique that illustrates how similar or different a set of genomes are to each other. The closer two points are on the graph, the more related they are. This can be seen in Figure 1 where the wild sheep genomes are highlighted in grey and the domesticated sheep genomes are along the bottom axis of the graph. The researchers found that the genomes from the Nachcharini Cave sheep were closer to the bottom of the graph where the domesticated sheep genomes are. This told them that these wild Nachcharini Cave sheep were the most genetically similar to the domesticated sheep, indicating that this region in the west of the Fertile Crescent was likely where domestication began.

Figure 1 from Daly et al. Above is a map depicting the locations of the sheep genomes with the Nachcharini Cave highlighted in a red box [B]. The graph shows principal component analysis of the ancient and modern sheep genomes [C]. The principal component (PC) number is labeled on the axis, and the percentage next to it denotes how much of the variance between the genomes can be attributed to this principal component. As the percentages are small, this indicates that the genomes are very different from each other. The authors conclude that domestication occurred in the west because the ancient sheep genomes found at Nachcharini Cave (located in the west of the Fertile Crescent) were more similar to the domesticated modern sheep, which are located at the bottom of the graph.

Another story that can be told from the genomes of these sheep is how their interaction with humans changed their appearance. Oftentimes, human pressures can aid in the selective evolution of certain traits in both animals and plants. A common example would be how dogs come in all shapes and sizes because they were bred by humans to look and act in certain ways. These same selective pressures were placed on sheep once they were domesticated by humans. By looking at how sheep genomes changed over time, the authors were able to see that shortly after sheep domestication there was selection for genes involved in coat coloring and patterning. As wool wasn’t typically used for clothing at this point in human history, the selection for coat color and pattern may reflect the desire of herders to make their own flocks distinct from other herders’. Alternatively, prehistoric humans may have chosen to heighten the aesthetic appeal of the sheep by selecting for beautiful and unique coat patterns. In either case, the interaction of humans and sheep in the Fertile Crescent greatly shaped how modern day sheep look today.

The results of this study highlight the historical storytelling power of genetics, and its ability to answer questions about prehistory. So, the next time you’re counting sheep to fall asleep, it might be worth thinking about how differently those sheep might look if humans hadn’t intervened.

Edited by Mandy Eckhardt and Jameson Blount

Leave a comment