Stories bring people together, help learners see deeper meaning, and provide much needed context to learning. In this examination of story, explore curricular ideas surrounding the discovery of the DNA double helix, and how the story of two female scientists have had such a huge impact on the world of genetics.

“Explain that scientific research and technological development help achieve a sustainable society, economy and environment”

(Alberta Education Program of Studies for Biology 20-30)

Taken directly from a curriculum document, this learning outcome emphasizes the importance of understanding scientific research and technological development in a high school biology course. As a teacher passionate about providing my students with a relevant, engaging, and meaningful learning experience, I choose to explore gene editing technology with them. Reflecting on my late undergraduate years studying molecular biology, I recall a special lecture from one of my professors on CRISPR-Cas9 gene editing technology—he was the first at the university to take it for a spin. This is part of my science story.

I invite you to step into my classroom and engage in this exploration with me.

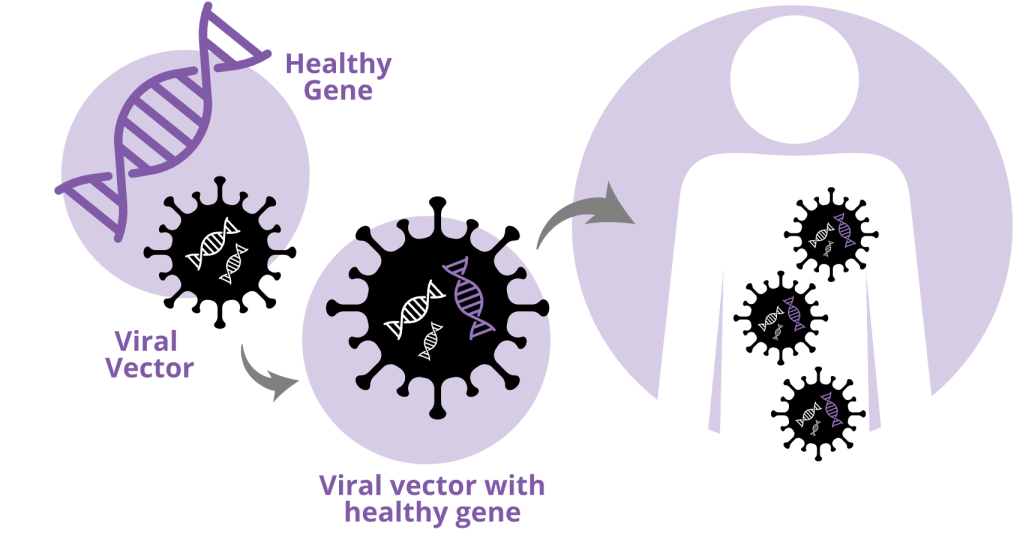

Recall the concept of artificial selection, (breeding organisms with desirable traits to get good offspring) taught in grade 9 science, and remember that humans have long attempted to alter genetics to our advantage. To emphasize relevance, remember its critical role in agricultural development, which is particularly important here in Alberta, Canada. For fun, we also explore its role in the breeding of your four-legged furry pets at home. As we progress through our case study, let’s learn about restriction enzymes, which cut gene fragments from chromosomes, and gene splicing, which allows us to insert genes of interest into model organisms for analysis. I share my personal experiences using this technology and discuss model organisms and their role in research. We talk about the cancer research I was working on and how it relates to the cell cycle and checkpoints. Next, we discuss Zinc-finger nucleases and their effectiveness, enhanced by advances in DNA sequencing technology. (For a detailed history of gene editing, see here)

As a student in my classroom, you can hopefully now see how we have evolved to a point where we have incredible ability to bend biology to our will. Now we finish with CRISPR-Cas9, an incredible force of nature; a system that can be customized by a scientist to cut and edit DNA quicker, more precisely, and more efficiently in comparison to previous technologies. To finish up any topic, you will always see a connection to social issues. We will have discussions and debates around the ethics of such incredible technology. Wrapping up, I recommend that this weekend you watch the movie GATTACA or I Am Legend to consider the impacts of genetics and technology on society in a fun and sci-fi way.

At this point, we’ve successfully met and exceeded the learning outcome above.

As I’ve matured as a teacher, I aim to go beyond meeting curricular goals to also engage learners in a more socially rooted conception of science. How do social contexts, struggles, and movements shape science, scientists, and breakthroughs? We’ve begun to explore social issues in the science classroom, but by delving deeper into the story, we can now examine social change. What follows are the insights I’ve gained while integrating the concept of the Nature of Science (NoS) into my teaching. NoS, often described as the “whole of science,” is crucial in science education. (I explain here.) As a doctoral student in curriculum studies, focused on identifying absent voices in what we teach in classrooms, NoS is vital for providing a comprehensive view of science. So, let’s dive deeper into the story of CRISPR and explore how we can educate about the issue of “Women Being Credited Less in Science Than Men.” Despite being the year 2025, this is a well documented problem.

Nobel Laureate Jennifer Doudna is a key figure in the discovery and application of CRISPR gene-editing technology. She notes in her reading of James Watson’s “The Double Helix” how impressed she was by the collaborative and social aspects of science and research—an important scientific lesson. These two stories we know are intertwined, and will be explored shortly. Unfortunately, she shares how, despite her aptitude for science and math, she was discouraged from pursuing it due to her gender. This experience is all too common, echoed by others I know, and by renowned women in STEM, such as Robin Wall Kimmerer.

Her biography on the Nobel Prize website highlights her commitment to women’s representation in science, and she praises Rosalind Franklin’s contributions to the discovery of DNA’s structure.Doudna had pivotal interactions with the discoverers of the DNA double helix, experiences that intertwined significant timelines and were crucial to her narrative. The story of Rosalind Franklin is particularly compelling and has gained prominence in education circles, especially with the rise of “Women in STEM” initiatives. Franklin’s contribution through her work in X-ray crystallography, especially her iconic “Photo 51,” was instrumental in Watson and Crick’s 1953 publication unveiling the double helix model. Despite the paper being cited nearly 20,000 times according to Google Scholar, Franklin’s contributions were not properly acknowledged. It is widely recognized that her work was used without her permission, and it provided the final piece to Watson and Crick’s puzzle.

Many people mistakenly believe that Franklin was unaware of the significance of her own work. This misconception leads to a portrayal of her as someone who didn’t fully grasp the impact of her discoveries, despite being celebrated for her role in a groundbreaking achievement. In my view, this diminishes her accomplishments and undermines the purpose of highlighting her as a pioneering example for women in STEM. It is crucial that her story is accurately represented, particularly in educational contexts.

Recent studies of Franklin’s notebooks and correspondences reveal that she was well aware of the significance of her work and its connection to the broader scientific picture, having made several key determinations similar to Watson and Crick. This challenges the narrative of “smart men” swooping in to save the day and piece everything together. Instead, it highlights a non-consensual collaboration where equal partners were not treated equally. In contrast, Doudna is a recognized name, having won a Nobel Prize for her discovery. However, a deeper look into her story reveals parallels to the mistreatment similar to Franklin.

When we consider these events, a fuller story emerges. It highlights progress but also underscores the ongoing need for change. Focusing solely on the marvels of CRISPR overlooks the important history leading to its discovery and the opportunity to address persistent disparities, biases, and systemic issues in the scientific community. When taught correctly, science can help remedy social injustices (see here, here and here for recent posts on this site). Importantly, students who learn about Rosalind Franklin’s story in biology show increased scientific literacy, which is the ultimate goal of science education.

Acknowledging these narratives allows us to critically shape a more inclusive future. Correctly attributing and celebrating with equal rigor, those women who are involved and make contributions are often the first step suggested in any discussion of meaningfully enacting change (examples here, here, and here). I would argue that this is not just true for women in science, but for all marginalized groups. This approach not only honors their contributions correctly but also inspires future scientists to pursue their passions without fear of bias. This paves the way for a more equitable future.

Edited by JP Flores & Jayati Sharma

Leave a comment