Stories bring people together, help students see deeper meaning, and provide much needed context to learning. In this “Decoding Life” series, I will examine topics we teach in genetics, and the full story behind those topics, beyond just curriculum. This holistic look at science helps improve scientific literacy and humanistic understanding of science.

“Let me tell you a story…”

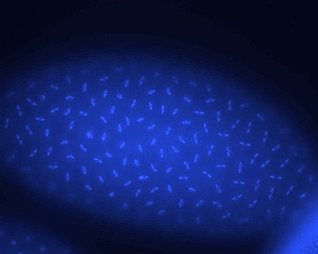

One might think that when a teacher says this, students’ eyes roll and there might be a collective groan. However, the right story might inspire and bring students in, resulting in deep learning. As a science teacher, the stories I tell come from experiences working in both Drosophila (fruit fly) and Danio rerio (zebrafish) genetics labs. A favorite of mine is telling the story of mitosis or the cell cycle, going back to Walther Flemming. Students are engaged and love to hear how such a significant discovery was made with such “limited” (their words) technology. As we travel the timeline and show how our understanding has increased, I tie in my own story of research. I discuss Drosophila embryos undergoing their rapid waves of mitosis and tie it to work I did looking at checkpoints that prevent the cell from advancing in the cycle until it is ready. It is important to show how scientists use model organisms like Drosophila to explore cellular processes, demonstrating the procedural nature of science. Finally, I love to show the following image:

Here you can see what happens when a checkpoint doesn’t happen, and cells divide inappropriately. Although not a human example, it still illustrates the point clearly… things get really messed up. Most people know that tumours/cancer develop from cells dividing inappropriately, or dividing infinitely. The image provided here, in my experience, resonates with students significantly, because they are looking at the molecular level and can see actual damage to a cell when mitosis doesn’t work. It’s not just a theory or idea.

Students are able to see the craziness of the real world, outside of the classroom, and outside of a textbook. Also, their teacher (me) “made” it. That adds a new level of meaning. All of this goes beyond curricular objectives of simply understanding the phases of the cell cycle. It shows processes and procedures and how we come to understand complex functions. It gives humanity to the concept of mitosis and a more complete picture its importance. I wish I had this in high school biology. Instead, I had to wait until my later years as an undergraduate to have this full and complete experience.

The Nature of Science (NoS) is an educational idea that involves providing the complete context of a scientific concept. It can simply be described as “the whole of science” or the “history, contemporary, inquiry” (I read this as past, present, future) of science. NoS encompasses everything. A story, organized into a beginning, middle, and end, provides this everything and acknowledges that science is not a linear process executed in a vacuum. It’s messy and has lots of diversions before coming to a resolution. A science story discusses collaboration, the critical thinking done by scientists, problem-solving mindsets, and the techniques and practices that can help solve problems.

Research shows many benefits to using stories in science classrooms. Stories connect content ideas from the science class to the chaotic messiness of the real world. Stories give the ability to see the true application of the content students learn, as opposed to simply just discussing or listing those applications in a list of curricular items. Students taught using storytelling devices reported improved learning experiences, because things were much more relevant and meaningful. This meaning is found as students hear stories and find people in them that are like them. Finally, stories provide social context, by situating the science in society, students are given tools to understand social situations.

As you can probably assume, these benefits extend past students in classrooms to anyone who would hear a science story. Researchers have found that stories have the ability to combat misinformation, improve reasoning skills, and increase scientific literacy in adult populations as well. These benefits have led media companies to offer opportunities to engage in story in meaningful ways.

The question then becomes, what stories should we tell? Dwayne Donald, Indigenous Canadian curriculum studies scholar, tells us that curriculum is: “the stories we teach our children about the world and our place in it”. This creates more questions than answers. How did the current content in a curriculum come to be there? What does the content in a curriculum say about the world that the learners live in and their place? This sheds a different light on the things that we teach in schools, which then turns into the knowledge and skills we equip students to enter the world with when they graduate high school. Much of our science curricula is memorization of facts and completion of labs with predetermined outcomes that aren’t really giving students meaningful experiences. Is that the story about the world that we want to tell? I hope not.

Ted Aoki, another curriculum studies scholar tells us that “science must be taught as a humanity“. This is the origin of my idea to communicate stories. Stories are typically used in the humanities. We study them in literature courses or social science courses, but not often in lab based science courses. Those who work in or study within science-related fields should understand the social nature of science, and the impacts that it has on people. Sometimes however, this is not always the case. I think all of us, scientists included, need some re-education here. Science is a social endeavour and the story matters. When we bring in stories, science can reach more people, not just the typical STEM nerds. Not everyone will have a STEM career. Not everyone has to memorize a list of science facts, but everyone needs to understand the processes and social nature of science and how it can benefit humanity. Stories provide this shared understanding amongst all people.

Going forward in this “Decoding Life” series, I intend to explore stories relevant to the field of molecular biology and genetics, which is the theme of this website. I intend to look at the “whole of science” in these stories, and identify important understandings that are often missed, as well as ways that these science stories can help us better understand and deal with social issues. I look forward to any feedback or ideas about the stories to explore. Stay tuned…

Leave a comment