The identity of a cell is dictated by the precise orchestration of turning on and off gene expression during development. Once a cell achieves its fated identity, it can’t be changed. The changing of cell fate was at first deemed incredibly difficult until an early 2000s paper proved this belief to be wrong – and ultimately won a Nobel Prize.

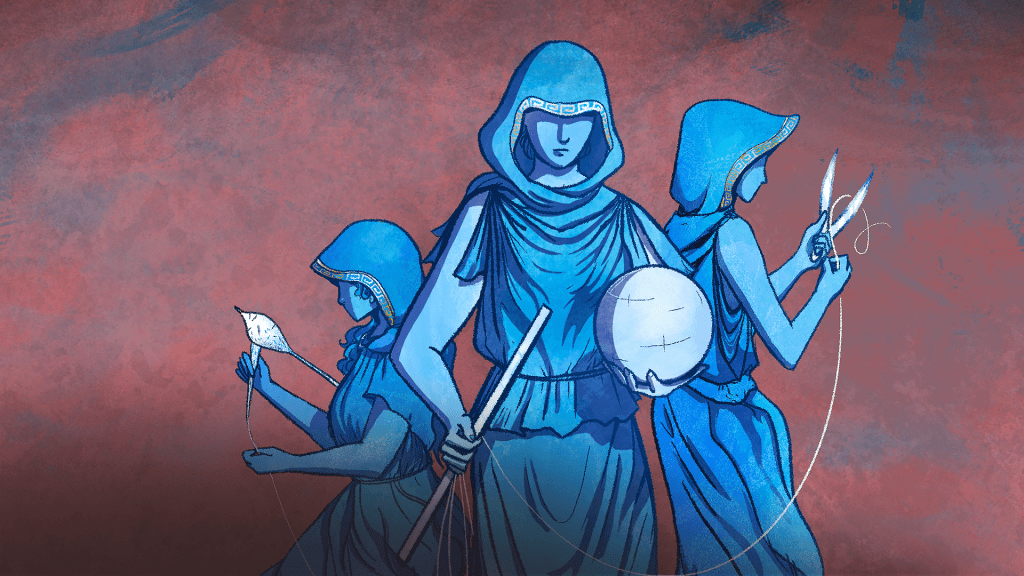

Image from PBS (https://www.pbs.org/video/the-fates-greek-mythologys-most-powerful-deities-tspxln/)

The concept of predestined fate is ubiquitous in many civilizations. Today, we might think of fate as something relegated to Greco-Roman times where the gods controlled our lives, and we accepted that fact – most of the time. Greek myth is filled with stories of kings and heroes attempting to change their fate – from the myths of Oedipus to the inception of the Greek pantheon with Kronos. In each story, the characters try and fail to change their fates.

What you might not know is that biology also has the concept of fate. While it’s not determined by three women snipping a thread, fate, instead, is determined by genes and the precise turning on and off of their expression during development. This is how a heart cell becomes a heart cell or a muscle cell becomes a muscle cell. Each cell type has a unique expression pattern of certain genes.

How do these cells get to this point? When a human is first formed, it’s a mere handful of cells that are described as totipotent. This means they can become any type of cell in the developing embryo, or they can become extra-embryonic cells (cells that make up the placenta or umbilical cord). As genes get turned on in these cells, they slowly take on their fated identity and lose their ability to become a different cell type. Eventually, each cell can only divide and make more cells of the same kind (with a few exceptions, such as stem cells).

At the beginning of development, cells are totipotent, allowing them to become any embryonic or extra-embryonic cell type. As the cells begin to differentiate, meaning they begin to take on a cell type specific phenotype, they become pluripotent and then multipotent. At each stage, they lose the ability to become a different cell type. Finally, cells become fully differentiated into a certain type of cell such as lung or skin cell. (image from https://www.technologynetworks.com/cell-science/articles/cell-potency-totipotent-vs-pluripotent-vs-multipotent-stem-cells-303218)

Just like the Greeks, we thought it was impossible to change the fate of a cell once it had fully differentiated into a specific cell type. A heart cell couldn’t become a liver cell no matter how many oracles it spoke to. That is until a paper was published in the journal Cell in 2006 by Kazutoshi Takahashi and Shinya Yamanaka that took the science field by storm and ultimately led to a Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 2012.

Pluripotent stem cells have always been important in clinical science. They’ve been used to treat a variety of diseases as well as in regenerative medicine to repair lost tissue. Pluripotency is one step below totipotency (as in the figure above). Pluripotent stem cells can give rise to any cell type except those considered extraembryonic like the placenta. In the past, the best stem cells to use for these purposes were embryonic stem cells: cells taken from an embryo. While there are many ethical issues with this approach, there are also practical ones such as the potential for rejection of these cells if they were transplanted into another individual. Another approach to generate pluripotent cells has been to merge fully differentiated cells with embryonic cells; however, this again brings up ethical concerns. Based on this past research, the authors of this 2006 paper hypothesized that there were factors present in embryonic stem cells that could induce differentiated cells to become pluripotent once more.

In this paper, Takahashi and Yamanaka took human cells and cultured them with a select number of transcription factors – proteins that help turn on gene expression – that are expressed in embryonic cells. They systematically added and removed 24 transcription factors to cell cultures, trying out different combinations to find the minimal number that would be necessary to convert a cell back to its pluripotent state. They found that they only needed four factors to change a fully differentiated cell back into a pluripotent cell. They called these cells “induced pluripotent stem cells” (iPSCs), referring to the way in which they reverted back to a pluripotent state.

To test that these cells were actually able to give rise to multiple cell types, as original pluripotent stem cells would, the authors injected the iPSCs into mice and allowed tumors to grow. Analysis of the tumors revealed that there were multiple cell types in the tumors from all three germ layers (red, yellow, and blue in figure above). This experiment confirmed that the cells had reverted to a pluripotent stem cell identity and could become almost any cell type.

While this paper only proves that differentiated cells can become pluripotent once more, the field of iPSCs has expanded since 2006. Now, iPSCs are used as a starting point to differentiate cells into various cell types for therapeutic or research purposes. In the lab setting, they can be used to model disease states or to test new therapies and discover novel drug treatments. They can also be used to build mini 3D organs which can further be used to study how diseases affect multiple cell types at once. On the therapeutic side, iPSCs are on the forefront of treating diseases and conditions such as diabetes, heart attacks, hearing loss, and bone grafts to name a few.

Even though Greek mythology tells us that our fate is set in stone, that isn’t true at a cellular level. We can turn skin cells into heart cells and back again if we please. Maybe we can’t control our fate, but we can at least change a very small part of it with the help of science.

Edited by Zach Patterson & JP Flores

Leave a comment