It’s your genome, how much do you want to know?

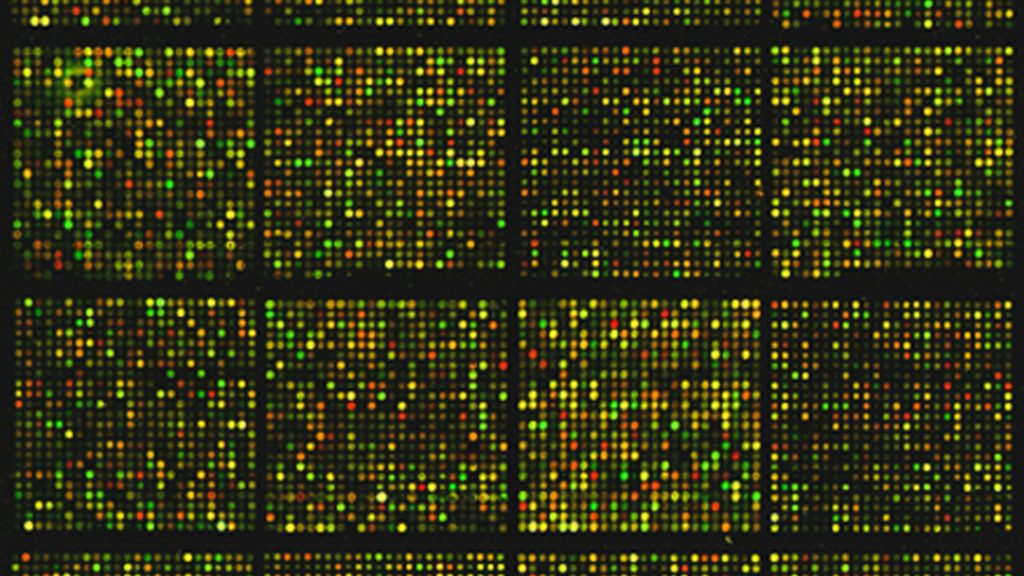

Photo by National Cancer Institute on Unsplash

Personalized medical care has been a dream for decades. Today, that dream is closer to reality with the rapid rise and increasing accessibility of DNA sequencing. It is now possible to sequence all of an individual’s DNA, also known as their genome, which can be used to diagnose patients with severe, difficult-to-diagnose disease when standard tests come up short. Cancerous tumors can also be sequenced to discover which medications they’re most likely to respond to. But once you identify the genomic sequences related to the primary issue, what do you do with all of the other information sequencing provides?

When doctors decide to use genomic sequencing, they’re looking at all of a patient’s DNA when there are likely only a few pieces that are involved with the primary issue. In some cases, like when a patient has symptoms of a disease known to be linked to a small subset of genes, doctors can choose to analyze the sequence of only those genes and not the entire genome. However, in cases of rare disease there has often been little to no research into their cause making it impossible to know where to look, so the entire genome must be investigated. This situation begs a question: once you find the few letters causing the problem, what do you do with the rest? You could analyze the entire genome, potentially finding risk factors for other conditions that could be life-changing for not just the patient, but their immediate relatives as well. Or, you could stop once you’ve found the cause for the current problem, leaving everything else alone. Perhaps it should be left up to the patient: learning that you’re at risk for certain conditions can be a scary experience, and reporting that risk requires great care by the physician to accurately communicate with accessible language.

Several national medical genetics organizations have laid out guidelines to deal with this exact situation. A review by Safa Majeed and colleagues compiled a list of policies published between 2005-2021 on how to deal with non-primary findings from genomic sequencing, defined as “incidental”, “secondary”, “unsolicited”, or “unexpected” findings depending on the policy. These refer to discovering variations in the patient’s genome unrelated to the primary reason for sequencing but which have some other scientifically-supported effect that can be treated or prevented. The most likely scenario is discovering variants that increase the patient’s risk for something common like heart disease, something that may not be immediately concerning but is important enough to start making lifestyle changes to minimize the risk of developing it. However, there could also be life-changing findings, such as the patient carrying risk variants for early-onset diseases like Huntington’s or Alzheimer’s. Different genetics-related organizations have very different recommendations for secondary findings: the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics (ACMG) advises investigating them only with the consent of the patient, while the European Society of Human Genetics (ESHG) recommends against any investigation at all, to the point of computationally filtering out any variants unlikely to be connected to the primary reason for sequencing. Both groups are trying to tackle the same concern: to avoid overwhelming the patient and the medical system due to diagnoses that aren’t actually affecting them. In the situations where genomic sequencing is being used as a diagnostic tool, the patient is already experiencing a severe illness. Telling the patient that they’re also at risk for something which may not affect them for years, whether preventable or not, is more likely to be an unnecessary layer of stress rather than a helpful precaution.

For patients who are interested in their secondary findings unrelated to the first reason they had their genome sequenced, it’s critical that they understand what exactly they can and cannot learn from their results. Nearly every policy agreed that patients should have a consultation with their healthcare provider prior to testing to discuss the risks, benefits, and limitations of genomic sequencing. Other information such as how their data will be used and protected, how their results will be returned, and how any follow-up analyses or contact will occur should also be discussed. These conversations are extremely important since some findings, like having early-onset disease variants, can impact immediate family members and not just the patient themselves.

Policies that recommend informed consent prior to secondary finding investigation outline different types of informed consent that healthcare providers can get from patients. The most straightforward is simple opt-in/opt-out consent, where patients either agree to receive all primary and secondary findings (opt-in) or choose to receive only primary results (opt-out). Another option is tiered consent, which allows patients to specify exactly what they do and do not consent to based on all possible choices. For example, patients could choose to receive only their primary results and early-onset disease risk secondary findings, but not common disease (e.g. heart disease) risk results. There’s also confirmatory consent, which asks patients again whether they want to receive secondary findings immediately before releasing their results. This gives patients the opportunity to change their minds after having time to think about the implications of potential findings.

Each consent option has its own pros and cons. Tiered consent puts the most power into the patient’s hands, but, depending on the patient’s knowledge of genomics, could require the most education from the physician on what information each tier could return. Alternatively, opt-in/opt-out could be the simplest to explain but may not fully prepare the patient for the volume of results they get back, and they may see every result as the same level of severity even if that isn’t the case. The review authors argue that regardless of the consent option chosen, confirmatory consent should also be utilized so that patients have time to digest information given in the original consent discussion, ensuring that they are truly prepared for the results they could receive.

Genomic sequencing provides a feast of information to doctors and patients which can be key in diagnosing rare or complex cases. However, the majority of information learned will be unrelated to the main reason for having the patient’s DNA sequenced. Many national medical genetics organizations have released policies regarding how this additional information should be dealt with, including whether it should be analyzed at all and how the results should be reported back to the patient. Majeed and colleagues found that organizations generally agree: it should be up to the patient to decide how much they want to know, and medical professionals should play a key role in educating and counseling patients and their families on the significance of any results the patient agrees to receive.

It’s your DNA, you should get to decide.

Edited by Zach Patterson and Jayati Sharma

Leave a comment