Scientists have recently shown that chemical modifications near your DNA, also known as epigenetic marks, affect how your body responds to viral flu infection.

Photo by RoadLight on Pixabay:

https://pixabay.com/illustrations/dna-double-helix-sustainability-5591477/

Why do some people get a terrible case of the flu while others barely respond to the infection? Perhaps you’re someone who has extreme responses to the flu— high fever, pounding headaches, and that awful “I’ve been hit by a truck” fatigue. Or maybe you are one of the lucky ones who barely gets a cough when infected. While some of these variances can be explained by different strains of the virus causing diverse effects in humans, even individuals infected with the same strain of the flu can display vastly different symptoms. Previous studies have demonstrated that environmental factors, gut microbiome diversity, sex, age, and host genetics can contribute to variation in the immune system’s response to flu infection. A recent Nature study led by Katherine A. Aracena of the University of Chicago has identified another previously unknown influence that impacts individual responses to flu infection: epigenetic variation.

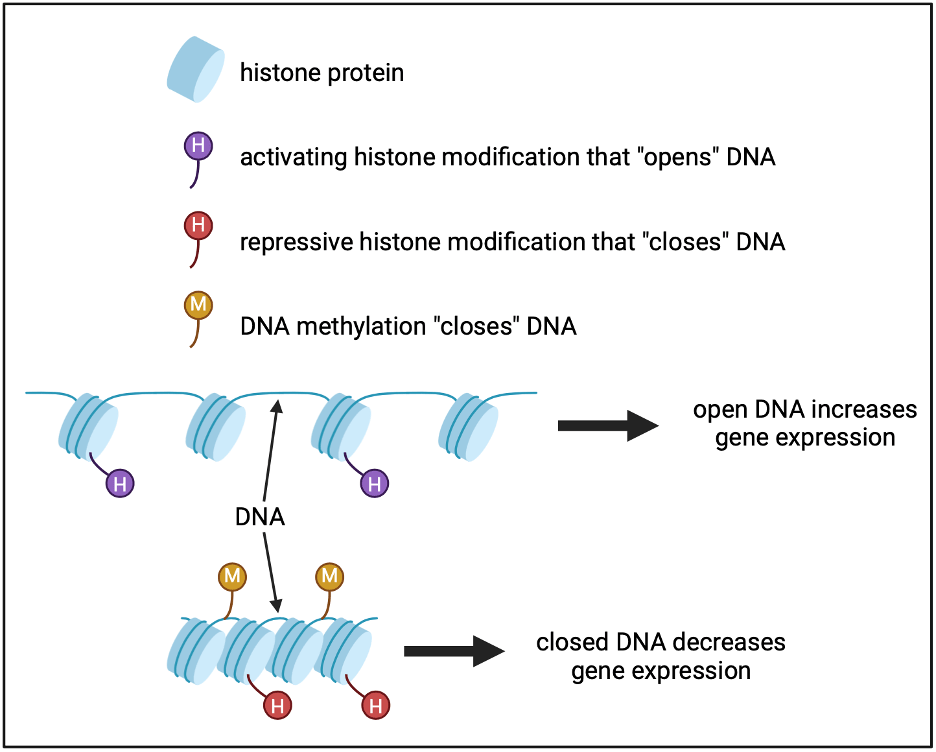

Differences in genetic code are known to cause variations in human appearance, disease susceptibility, behavior, and as previously mentioned, immune response. However, Aracena and colleagues show that a lesser studied, but highly important, piece of the puzzle, known as epigenetic variation, also contributes to each individual’s unique immune responses to flu infection. The term epigenetics literally means “above the genetics,” and refers to chemical marks that do not change the genetic code itself, but rather alter how the genetic code is utilized by the cell. These chemical marks can be found directly on DNA, such as DNA methylation, which is when a carbon atom is directly bound to DNA. Epigenetic marks can also be found on histones, the proteins that DNA wraps around to organize it into chromosomes. The function of epigenetic marks is to alter DNA accessibility, meaning they “open” or “close” the DNA. Genes with activating epigenetic marks open DNA and increase gene expression, while genes with repressive marks close DNA and decrease gene expression.

Figure created using BioRender.com

To understand how epigenetic variation affects immune cell response, the research team acquired macrophages, a type of immune cell, from 35 male volunteers of African and European ancestry. These macrophages were infected with flu virus for 24 hours. The flu-infected macrophages were collected and compared to uninfected macrophages in a variety of genetic and epigenetic analyses. Interestingly, infected versus uninfected macrophages show significant changes in gene expression. In particular, genes that play an important role in immune and inflammatory responses showed increased gene expression in flu infected macrophages compared to uninfected macrophages. Flu infection also caused variation in DNA accessibility. Activating marks on histones, such as acetylation, were found to significantly differ between infected and uninfected macrophages. Oppositely, repressive marks on DNA and histones displayed very little change upon flu infection.

The research team also examined epigenetic differences between macrophages obtained from individuals with European versus African ancestry. Previous data has shown that genes involved in inflammation display increased expression in individuals of African ancestry, but it was not previously known whether these changes in gene expression are caused by epigenetic variation. Strikingly, compared to individuals of European ancestry, individuals of African ancestry exhibited increased DNA accessibility and activating epigenetic marks, specifically nearby genes involved in inflammatory response, though the exact mechanism is yet to be discovered. This result suggests that epigenetic variation, at least in part, contributes to the previously observed rise in gene expression of inflammatory genes in individuals of African ancestry.

After seeing differences in epigenetic status between African and European ancestral backgrounds, the researchers reasoned these variations may be due to differences in the genetic code. In some cases, they discovered a significant correlation between differences in the genetic code and epigenetic variation at the same regions of DNA across individuals of African and European ancestry. Specifically, the genetic differences between African and European ancestry samples contribute to 65% of the identified DNA methylation differences between them. However, variations in epigenetic marks on histones between African and European ancestries only correlated with genetic differences in 17-29% of cases. Further, a subset of inflammatory response genes with varied epigenetic patterns between African and European individuals did not correlate with changes in the genetic code. Taken together, this data suggests differences in genetic code can facilitate some, but not all, epigenetic variation, while ancestry-associated differences driven by environmental factors likely account for epigenetic differences not associated with genome changes.

Finally, this work examined the association between the heritability of epigenetic variation and the different levels of the immune response. Multiple immune disorders showed significant correlation between epigenetic status and heritability. Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis showed the strongest correlations, suggesting that susceptibility to gut inflammatory disorders in particular is affected by the epigenetic status of macrophages.

The research team notes that epigenetic variation may not directly cause changes in gene expression associated with disease traits. Rather, epigenetic features likely alter how accessible the DNA is to transcription factors, a group of proteins that can increase or decrease gene expression. For example, epigenetic marks that cause DNA to become more “open” would allow activating transcription factors more access to the “open” DNA than “closed” DNA, thus promoting gene expression. However, more research is necessary to confirm whether this hypothesis is true.

Although a variety of different features have been shown to affect susceptibility to flu infection, this new research highlights epigenetic variation as another factor in human immune responses. Another extremely impactful aspect of this study is the focus on identifying genetic and epigenetic differences across individuals of African and European ancestry. Historically, data from individuals with non-European ancestry has been quite limited, causing blind spots in the efficacy and potential impacts of medicines and treatments given to people with non-European backgrounds. Although additional and continued efforts are necessary to eliminate such research disparities, this study contributes to filling the gap in our scientific and medical knowledge of individuals with non-European ancestry.

So, next time you get sick with the flu, whether you are barely affected or develop strong symptoms, you can surely know that your epigenetics are playing a role in the specific response your body exhibits, and in the future, we may be able to utilize this knowledge to develop better and more personalized treatments for all humans.

Edited by Richard Coca, Jayati Sharma & JP Flores

Leave a comment