A recent study by Polinski et al. reports the first full genome sequence of an extraordinarily long-lived sea urchin species, revealing genetic factors that may play a role in increased lifespan and reduced disease.

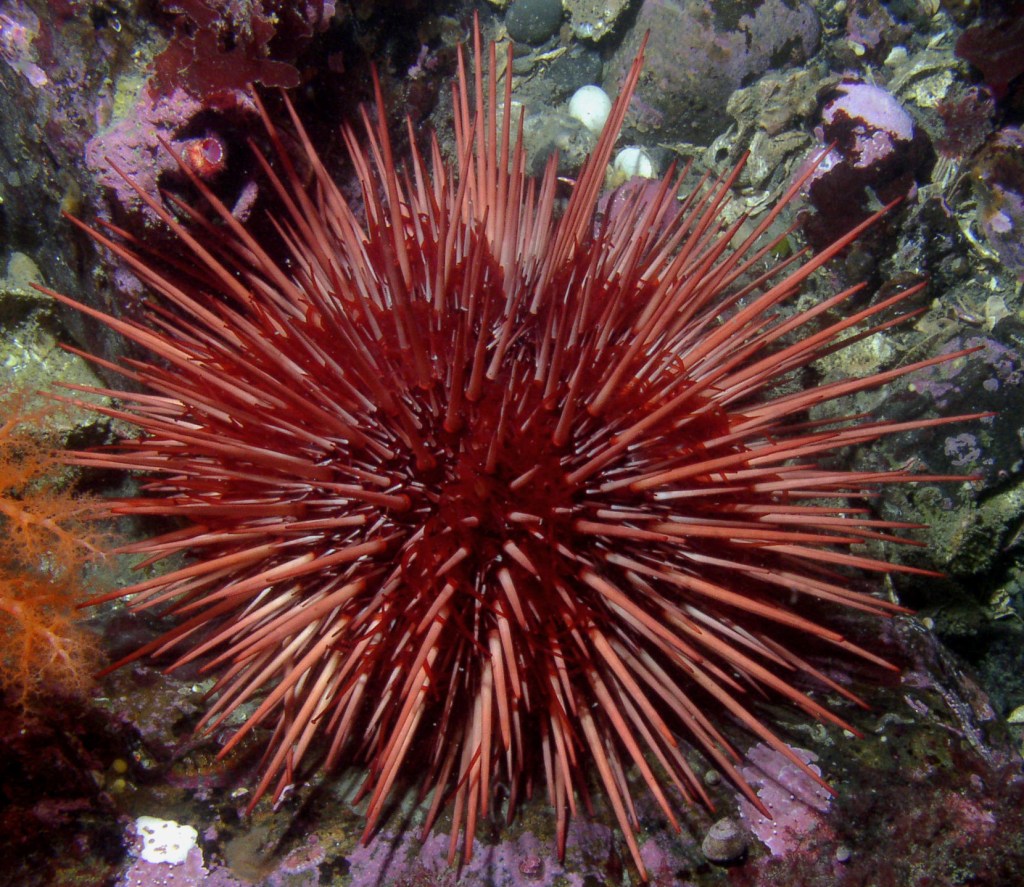

[Photograph by Kirt L. Onthank, CC BY 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons]

A few years back, a good friend of mine sent out a birthday invite that started, “As many of you know, I am constantly increasing in age.” An incontrovertible truth! Also made me laugh. But what if we could age chronologically while avoiding the physical changes that accompany aging?

The quest for immortality reaches back millennia, from tales of Gilgamesh dating thousands of years BCE, to the Holy Grail of Arthurian and Monty Python legend, to the Philosopher’s Stone of Magnum Opus and, more recently, Harry Potter fame. While these existed in the realms of mythology and alchemy, today there are very real efforts underway to understand – and potentially halt or reverse – the cellular and molecular processes that contribute to aging. And some of these efforts have very real financial backing, with support from the likes of tech giants Jeff Bezos of Amazon, Sam Altman of OpenAI, and Google’s parent company, Alphabet.

The goal of substantially increasing the maximum lifespan that humans can achieve is wrought with ethical questions. Who would have access to such interventions? How might they impact challenges related to population growth? Would societal progress and social change be affected if generational turnover is slowed? Could it change what it means to be human? These are important questions that deserve careful consideration. Nonetheless, a better understanding of processes that underlie aging could also lead to interventions that increase quality of life into old-age – one’s “healthspan” – without lengthening lifespan, by reducing the incidence of age-related disease. So, dreams of immortality aside, what do we know about the molecular basis of lifespan and aging? And can we use this information to increase our “healthspan”?

Molecular basis of aging: what we know and how we learned it

There are a dozen or so changes in cellular and molecular processes that have been dubbed “hallmarks of aging”. These changes generally reflect the deterioration of normal cellular functioning with advancing age, and interfering with them can speed up or slow down the aging process. Some hallmarks of aging include the accumulation of damage to DNA, alterations in gene regulation, and an accumulation of damaged or non-functional proteins. All of these changes are thought to hinder the proper functioning of individual cells, which in turn affects the tissues that they make up, and ultimately the organism as a whole.

How were these hallmarks of aging identified? Over the last few decades, several lines of research have given us a glimpse into the molecular basis of aging. Some of the earliest work focused on laboratory model organisms, including the nematode worm C. elegans, fruit flies, and mice, identifying mutations in individual genes that extended the lifespan of these animals. More recently, with advances in DNA sequencing technology, researchers have been able to search through full genome sequences for signatures associated with longevity. In humans, this has been done with the aim of identifying any specific gene variants that are found in people who live very long lives. In other animals, studies have compared the entire genomes of related species with differing lifespans to identify genetic traits unique to long-lived species.

Sea urchins crawl onto the aging scene

A recent study by Polinski et al. has taken advantage of this latter approach, and highlighted the potential usefulness of an underappreciated – and perhaps unexpected – phylogenetic class in aging research: sea urchins. Sea urchins are spike-covered, ball-shaped animals that live on the seafloor and feed primarily on kelp and algae, but also pretty much anything else they encounter, like plankton or molluscs. They belong to the phylum echinodermata, which also includes starfish and sea cucumbers. There are nearly 1000 species of sea urchin, which can be found in oceans around the world, at a wide range of depths. And – key to this study – they have an enormous variation in lifespans, ranging from just a few years in some species, to the red sea urchin that can live upwards of 200 years.

To try to understand why the red sea urchin can live for such an incredibly long time, Polinski et al. completed the first reported full genome sequence for this species, and compared it to previously sequenced genomes from other very short-lived (~5 years) and long-lived (~50 years) sea urchin species. With this comparative lens, they used two different analytical tricks to try to uncover genes that might contribute to the longevity of the red sea urchin compared to its cousins. First, they searched for genes that showed a signature of “positive” evolutionary selection in the red sea urchin. These are genes with adaptations that are presumed to provide a fitness advantage to the organism, and which might contribute to its unique traits; on a technical level they are identified as genes whose DNA sequence has mutated in a way that changes the sequence of the encoded protein – thereby potentially altering its function – more than would be expected by chance alone. Second, within each sea urchin species they identified all of the families of related genes (i.e. homologous genes), then compared these gene families across the different species, looking for those that were expanded (or shrunk) in the red sea urchin.

Together, these analyses uncovered a number of gene families that appear to be specialized in the red sea urchin. Since the methods used just looked for any genetic traits that were unique to this species, there’s no guarantee that the genes identified play a role in aging as opposed to other aspects of the red sea urchin’s biology. However, strikingly, many have functions that could contribute to an increased lifespan. These include genes whose functions may counteract some of the molecular hallmarks of aging mentioned above, with roles in the repair of damage to DNA, regulation of gene expression, and the clearing out of cellular junk in the form of misfolded or non-functional proteins. In addition, dozens of gene families with roles in more systemic organismal processes were expanded in the red sea urchin, including those with roles in innate immune function and the sensory nervous system, both of which could be imagined to increase lifespan by protecting sea urchins from external threats.

The search will continue…

So, do these clues to the secrets of long life from the red sea urchin bring us closer to increasing human lifespan, or healthspan? Maybe – but not likely any time soon. However, they certainly do open up new avenues for future research. For instance, while some of the specific genes identified in this study have been previously implicated in lifespan extension in other animals, others represent new potential candidates for the control of longevity. And more generally, this study highlights the potential usefulness of sea urchins for uncovering mechanisms that contribute to longer life. Given the large number of sea urchin species in the world and their wide range of lifespans, deciphering the genome sequences of additional species will only increase the power of the comparative approach undertaken by Polinski et al.

While sea urchin research is, admittedly, less likely to yield immediate medical interventions to slow aging than the focused research efforts of biotech companies with billionaire investors, the comparative genomics approach used by Polinski et al. has the advantage of leveraging strategies that nature has already developed to gain novel insights into the aging process. And along the way, outside of any potential future medical utility, Polinski et al. have highlighted some interesting aspects of the biology of an extraordinary animal. Sometimes research – like life – can be as much about the journey as the destination.

–

Edited by Mandy Eckhardt & JP Flores

Leave a comment