Researchers have discovered that while roots above-ground and below-ground show clear differences at the surface level, such as the cells they originate from, they share more genetic similarities than previously thought. This sheds more light on how plants adapted and developed specialised roots for different environments.

Picture Credit: Atanas Paskalev from Pixabay

Stem cells have diverse applications and an easy-to-shape nature. They can become heart cells, liver cells, nerve cells, you name it! Plants show a similar adaptability to their conditions and environment, wherein, they can develop new “organs” (in terms of plants that grow seeds, these are shoots, roots, and leaves) on demand! Truly the Netflix of organs.

But, just like in the case of humans, these organs have to be specific to the function they have to fulfill. Heart cells can’t be substituted for nerve cells, and vice versa. In this sense, not all roots are created equal either. And yes I did say roots, as in several types. We look at three kinds in this article: shoot-borne (which are above ground), lateral (which are below ground), and wound-inflicted roots (which are largely above ground and shoot-borne but can also be below ground, depending on the site of the injury).

Picture credit: “Forming roots from shoot” by Lidor Shaar-Moshe and Siobhan M. Brady

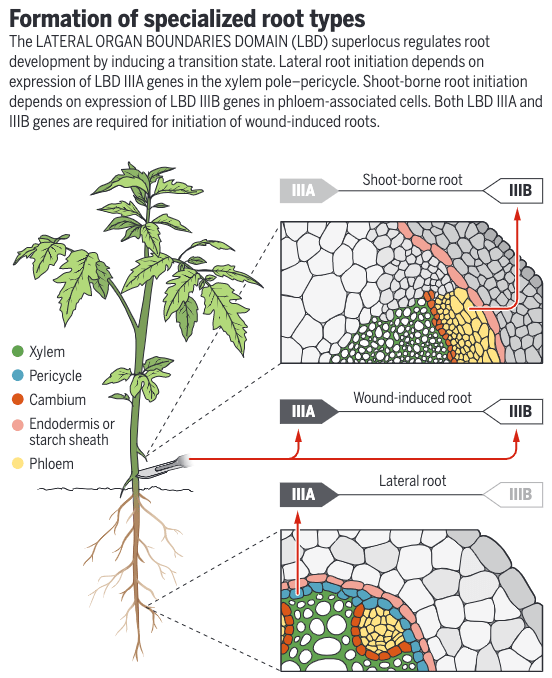

But… aren’t they all roots? Granted they may originate due to different requirements and perhaps even from different parts, as their names imply, but aren’t they still the same “organ”? Shouldn’t they have something more in common than just the name of roots? And to that, a few researchers said actually, yes! In a new paper published in Science, researchers found a common link, a common transition state, between the initiation of growth of these roots. They were also able to identify the genes that regulate this growth.

Researchers showed that these three roots have a common transition state. Buried deep in the genes that control the growth and regulation of these roots in angiosperms (i.e plants that bear flowers), they identified a superlocus of genes. A superlocus is like the point of intersection in a Venn diagram; it is a position on a chromosome that is part of many genes. The superlocus here contained genes from two different families of genes. Each family is specialised to control the growth of different kinds of roots and proteins, with one controlling shoot-borne roots and the other wound-induced and lateral roots. The proteins in question are called SHOOT BORNE ROOTLESS (SBRL) (say that three times fast!), named so because in the absence of this factor, no shoot-borne roots were seen, and another related protein called BROTHER OF SBRL (BSBRL) (botanists should really name everything). It follows that genes in the family controlling shoot-borne roots are actually able to do so by regulating the function and expression of SBRL, while a similar case applies to wound-induced and lateral roots and BSBRL. This particular superlocus was of interest because it controls the expression of both of these characteristic proteins as it contained genes from both families. To verify this, researchers grew mutants of the tomato plant that lacked this superlocus, and as a result no shoot-borne, wound-induced or lateral roots were seen. Only the embryonic root grew.

What’s more is that this superlocus seems to be ancient in its design, like a well-preserved artifact that has worked for eons without much change or improvement required. Researchers were able to test this experimentally by extracting this superlocus from the tomato plant and introducing it in Arabidopsis. These species diverged nearly 120 million years ago, and both have different genes, specific to the plant, to regulate root formation. And yet, the tomato superlocus was able to drive the expression of growth hormones in the initial growth of the root in Arabidopsis. If it ain’t broke don’t fix it, am I right?

This superlocus also seems to be highly conserved (i.e, not significantly changed throughout the years), as proposed by the researchers here, because a lot of different angiosperms have genes from the first family that are closely related to a gene from the second family and both of whom are located right next to each other on a single superlocus. One family was entirely missing in two carnivorous plants and one water plant, all three of whom lost their roots at some point in evolution, which further cements the inalienable nature of this superlocus and its role in root formation.

The versatile nature of these roots has greatly aided plants in surviving and adapting to various environments. Owing to the common transition state, the plants don’t have to make an early choice on what kind of roots to grow, and because of the superlocus genes involved, they are able to specialize their roots according to the needs their environment presents. This flexibility of choice is enabled by the genetic mechanism underlying root formation.

Maybe plants could offer Netflix some tips on improving their algorithm. Then again, maybe a plant with a million-year-old genetic mechanism that has stayed relatively unchanged would not have the best advice.

Edited by Jayati Sharma & JP Flores

Leave a comment