Only about 10% of drugs that enter Phase I clinical trials end up approved, and many trials are stopped prematurely. In a new study, a team of researchers found that clinical trials that were stopped early had lower odds of being supported by genetic evidence.

Photo by Pixabay on Pexels.com: https://www.pexels.com/photo/person-in-white-hand-gloves-writing-on-white-paper-207601/

Advancements in biomedical research offer hope for treating many diseases within the population. However, the vast majority of clinical trials don’t end up yielding an approved drug . These failures can result from issues with the drug’s safety or effectiveness, funding problems, patient eligibility criteria and recruitment, patient dropout, and more. Investigations of studies published in recent decades have also highlighted the prevalence of fake or highly flawed clinical trials, which can negatively impact health outcomes.

Identifying commonalities in failed studies could potentially help guide future study design for improved success rates. Researchers from Open Targets, the European Molecular Biology Laboratory, and the Wellcome Sanger Institute sought to do just that.

The team used a type of artificial intelligence called natural language processing (NLP) to sift through 28,561 clinical trials reported on ClinicalTrials.gov and categorize why they were stopped. NLP models human language in order to interpret and produce text or speech, so it can read across the high volume of trials and assign each to a group based on the reason for its failure. The investigators trained the model for this task on a set of stopped clinical trials that had been manually classified.

Over one third of the trials with a recorded stopping reason were classified as halted due to “insufficient enrollment”. Much smaller fractions were halted due to “safety or side effects” (3.38%) or “negative” [i.e. trials that are non-efficacious or non-valuable (7.6%)] reasons, which is far lower than other previous reports suggest. Early consideration of logistical and other non-scientific concerns may therefore be useful in determining whether to begin a clinical trial.

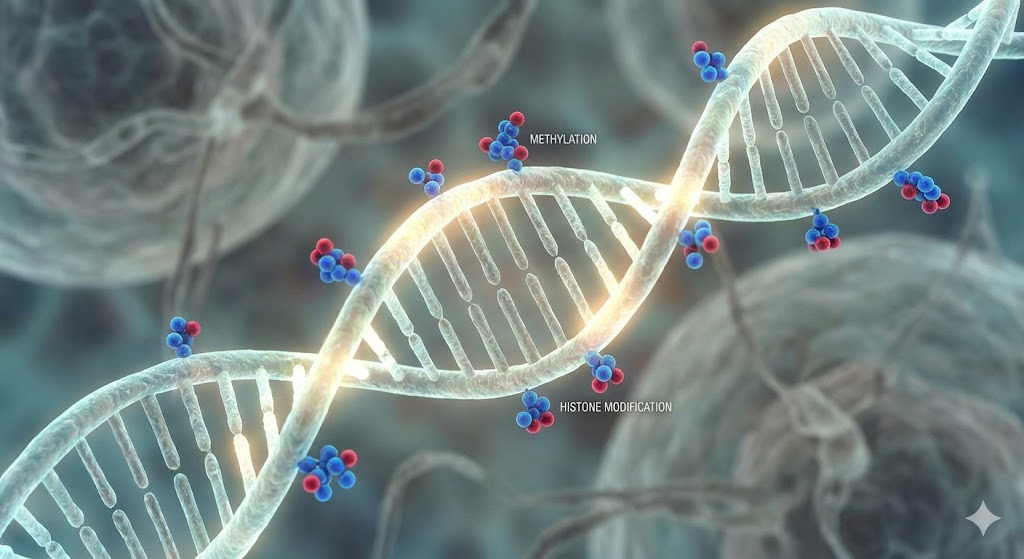

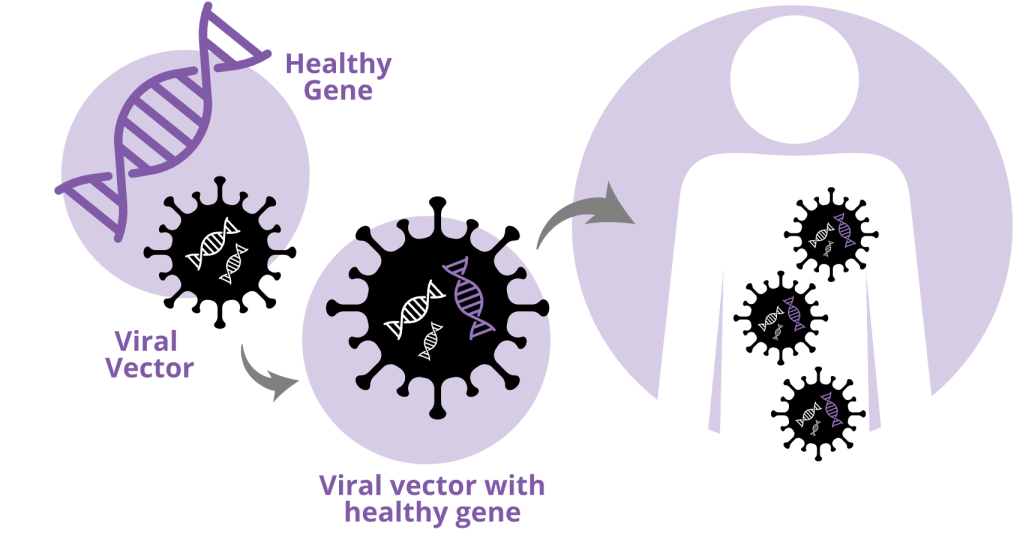

Previous work has shown that drugs whose targets are backed by genetic evidence have a higher chance of becoming approved. Therefore, the researchers decided to investigate the presence or absence of genetic evidence for the stopped trials. They used information about human gene-disease relationships and mutations from several databases, as well as genetic data from mouse models of human diseases. They found that trials that were stopped were less likely to have biological targets that were supported by genetic evidence. This was the case for studies stopped for some health-related (e.g. safety and efficacy) and some non-health-related (e.g. administrative and insufficient enrollment) reasons, although not all these trends were statistically significant.

Both cancer-related and non-cancer-related studies that were stopped because the drugs didn’t work or the study was evaluated as futile were less likely to have genetic evidence support. The risk of a clinical trial stopping due to “safety or side effects” was also associated with genetic factors. For example, when looking collectively at cancer-related and non-cancer-related trials together, there is a higher likelihood of a trial stopping due to safety reasons if:

- The target gene is highly constrained, meaning that it does not show much variation in a population

- The target gene is loss-of-function intolerant, meaning that mutations that disrupt its function are not frequent in a population

- The target gene is expressed (i.e. used by the cell) in many types of tissues rather than a specific subset of tissues

- The product made using a target gene is known to interact with a lot of other molecules in the cell.

Notably, when looking only at non-cancer-related trials alone, these trends either are not true or do not reach statistical significance, demonstrating that the cancer studies have a large impact on trends among all safety-stopped clinical trials.

The researchers acknowledge that there are limitations to this study. Firstly, factors in the cell other than the direct drug target may impact trial outcomes. Additionally, the researchers found associations between genetic evidence and trials stopped for non-biological reasons (e.g. trials stopped due to low enrollment had less genetic evidence), suggesting that the official record of stoppage reasons might not always include all actual reasons for stopping.

Nevertheless, these results highlight the importance of considering what’s known about gene targets for clinical trials when deciding whether or not to move forward with them. Since the clinical trials for development of a single drug cost millions of dollars, the high occurrence of failure represents a huge financial loss. The finding that clinical trials with less genetic evidence are more likely to be stopped suggests that finding stronger support for gene-disease associations should be a higher priority in the lab-to-clinic pipeline.

Edited by Zach Patterson and Jameson Blount

Leave a comment