Rare diseases involving the nervous nervous system, such as Timothy syndrome, remain largely mysterious, but groundbreaking research using 3D brain organoids and a new class of therapeutics holds promise for improving health outcomes.

According to the National Institutes of Health, between 25 to 30 million Americans suffer from a rare disease, almost half of which involve the nervous system. Despite their prevalence, we know very little about the mechanisms of these rare neurological disorders, let alone their cure or treatment plan. This was the case for Timothy syndrome, also known as long QT syndrome, which has never had more than 70 diagnosed cases. Children with this disorder rarely survive to late adolescence. Timothy syndrome is caused by a mutation in the CACNA1C gene, which codes for a calcium channel crucial for neurotransmitter release. Mutations in the calcium channels can lead to faulty neurotransmission in the central nervous system and in the heart. When CACNA1C is mutated, an individual can present with autism, epilepsy, severe heart issues, and schizophrenia.

A growing body of work led by Stanford Neurobiologist Dr. Sergiu Pasca has examined exactly how the CACNA1C mutation affects Timothy syndrome, using cell culture, brain organoids, and rat models. Building on this effort, they recently extended their work to explore promising therapeutic approaches for this rare and detrimental disease.

In 2011, Pasca and his team were one of the first few people to successfully generate neurons from iPSCs derived from patient fibroblasts. Patient fibroblasts are derived by skin biopsied from patients. These fibroblasts are then changed into induced pluripotent stem cells (IPSCs), which can then turn into any type of cell in the body. In this case, iPSCs were converted into neurons. From these neurons, scientists learned that the calcium ion channels stayed open for longer in Timothy’s syndrome. However, the use of 2D culture – studying these neurons on a dish – proved challenging given the short life of these neurons. This challenge prompted innovation as Dr. Pasca and his team raced to find transcription factors that would allow the engineering of three-dimensional (3D) brain organoids instead. These brain organoids represented different parts of the brain like the cortex and subcortical regions. Getting these complex, distinct brain regions to work together in a singular model would not happen until 2017.

This consolidation required assembling brain region-specific organoids into large 3D cultures known as assembloids. The assembloids of these different brain regions revealed novel insights into how Timothy syndrome led to its pathology. In Timothy syndrome assembloids, some of the neurons failed to migrate to the cortex. When neurons fail to migrate to the correct brain region, they can’t form the correct connections, which can lead to cognitive and developmental problems.

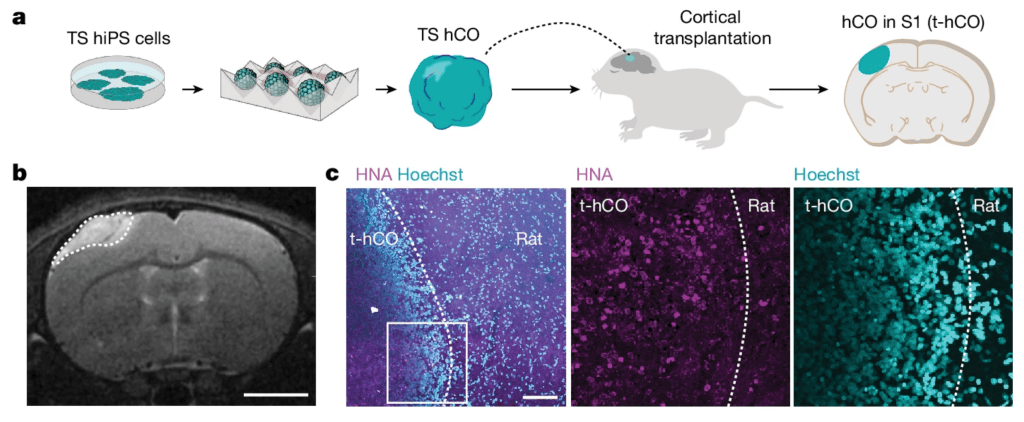

Though these assembloid-based insights were novel, they didn’t reflect mechanisms in a live organism. In 2022, Pasca and his team transplanted human cortical organoids into rats’ brains, which resulted in the integration of human neurons along with supporting brain cells into the brain tissue of rats to form hybridized working circuits. The transplanted neurons showed complex branching patterns that better represent what happens in vivo in humans with Timothy syndrome. These neurons also show differences in the electrical activity generated from neurons derived from Timothy syndrome patients.

Having identified major components of the biological pathways underlying Timothy syndrome, Pasca and his team have recently begun exploring possible therapeutic approaches for this rare disease.

Just last month, Pasca and his colleagues demonstrated, in principle, that antisense oligonucleotides (ASOs) can correct the fundamental defects that lead to Timothy syndrome by nudging calcium-channel production toward another form of the gene that does not carry the disease-causing mutation. ASOs are short oligonucleotide sequences that bind to mRNA and can “reduce, restore, or modify protein expression”. In this case, the authors used ASOs to guide production of the functional rather than defective form of CACNA1C, which reversed the defect’s detrimental downstream effects: The ASO nudge restores the electrical properties of the calcium channel to normalcy. The ASO’s efficacy was demonstrated in vitro — and, critically, in vivo via the rat-transplantation experiments, suggesting that this therapeutic approach can work in a living organism. This use of ASOs is likely to benefit other rare diseases.

Rare diseases are often caused by missense variants that lead to too little or too much of a protein being produced. ASOs for variants in genes under study, like RHOBTB2, SYNGAP1, and UBE3A, may prove beneficial to several rare diseases. These ASOs all seek to restore protein levels to normal in hopes of benefiting patients with these genetic disorders.

Edited by JP Flores & Jayati Sharma

Leave a comment