“This is a question I’ve had since I was a little kid.” Xia described this as a curiosity-driven project that was conceptualized after sustaining a tailbone injury in an Uber in May 2019.

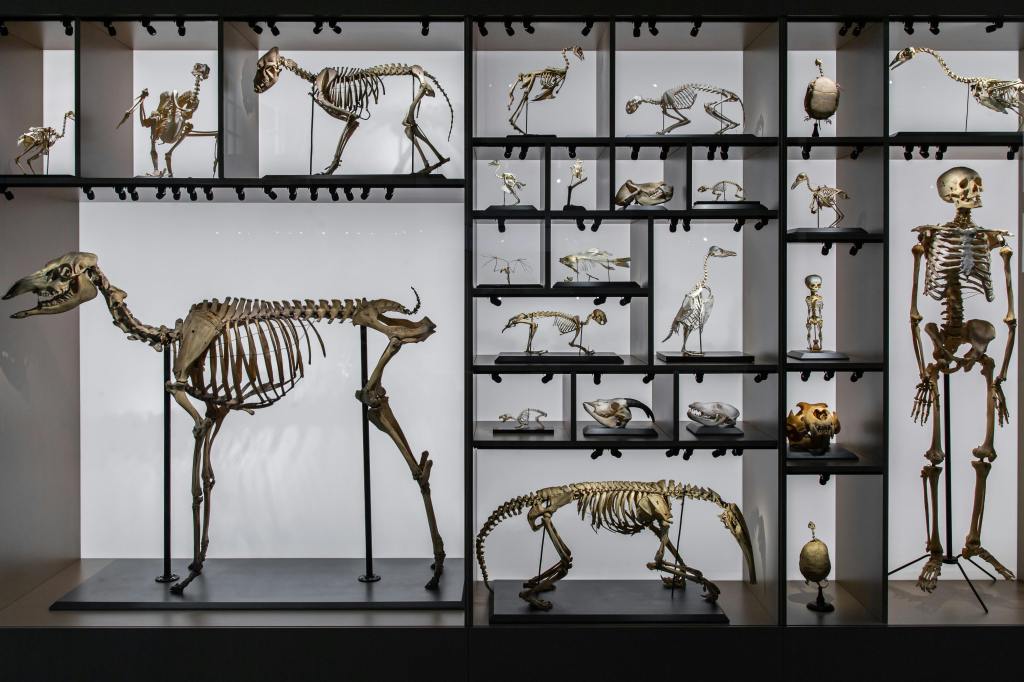

(Photo by Max Mishin: https://www.pexels.com/photo/dinosaur-and-human-skeletons-12227297/)

If we were to turn back time about 30 million years and trace the evolutionary footsteps of our ancient ancestors, we would see a world where tails were once a common feature among primates. About 25 to 20 million years ago, hominids diverged from their last common ancestors of primates and gave rise to humans and apes. Fast forward to today, and you’ll find that tails are a common feature in vertebrates throughout the animal kingdom, where most mammals, including humans, have tails at some point during embryonic development. We lost our tails over evolutionary time, and evidence resides in the form of our tailbones …but how exactly did it happen?

In a recent study published in Nature, Dr. Xia and colleagues found a genetic underpinning for tail loss in humans. “This is a question I’ve had since I was a little kid.” Xia described this as a curiosity-driven project that was conceptualized after sustaining a tailbone injury in an Uber in May 2019. He became curious about how we lost our tails, and a couple of months after the accident, he began sifting through the literature. He pitched this project to his principal investigator (PI) and collaborators, and with their support, they started collecting preliminary data later that year. They were off and running to figure out the genetics of tail development and what changed in the lineage of hominids.

“We have the genetic sequence for humans, apes, and monkeys. We have the tools to compare genes and genomes.” After performing comparative analyses, Xia found many hominid-specific genetic mutations and structural variants. He explained that the interpretation of these differences across species is critical and allows us to craft a story behind the genes that led to hominid tail loss. One of the gene candidates they decided to study was well-documented in playing a role in tail development, TBXT. TBXT is the gene behind the protein brachyury, which translates to “short tail” in Greek. Xia explained that this was a prime candidate gene because the gene and protein are known for stunting tail development in many species such as cats, dogs, and sheep. “If they have short tails, it’s usually because of a mutation in TBXT.”

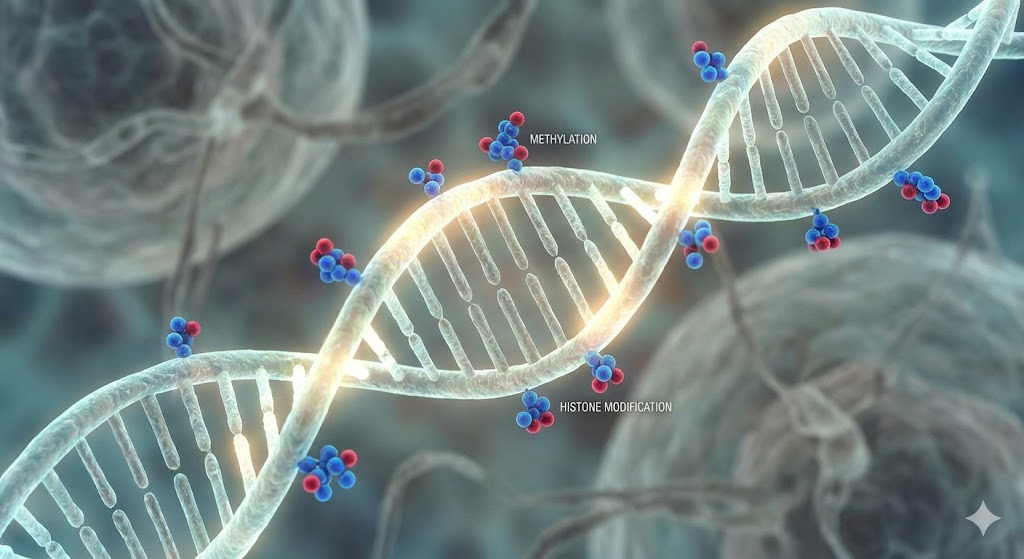

One mutation was found within a non-coding region of the TBXT gene. Xia’s first thought was “Oh, but it’s in an intron, it shouldn’t matter”, but a “Eureka!” moment happened on a Friday night while he was perusing this gene region comparing humans, apes, and monkeys. “It was the moment where everything made sense to me.” He discovered that this mutation was a DNA sequence called an Alu element, that was flipped around in a nearby part of the gene, so that sequences were facing each other. Xia thought that when the gene was copied into mRNA, these Alu elements might stick together, forming a loop-like shape. This loop would cut out a part of the gene, making a shorter version that could affect how tails develop. He hypothesized that monkeys would make the longer version, while humans and similar animals would make the shorter one. Xia then showed that both Alu elements were needed to make these different versions of the gene, and changing them affected the length of tails in mice. The group also found that mice with shorter tails had different versions of this gene, and just swapping the Alu elements with similar sequences was enough to change the tail length.

As a result, the team found that this seems to be a very important mutation that relates to tail loss in hominoids. Xia credits this finding to his mentors who were supportive in him pursuing the work, despite their lack of extensive knowledge on the subject matter. Xia wants to emphasize that this is just one piece of the tail development puzzle. “Across evolution, there’s probably many more mutations. Something else must’ve happened to ensure tail loss stability.” The tail loss and short-tail phenotypes in the mice models were not consistent, suggesting different or additional mechanisms for stable tail loss in humans. Nonetheless, this is the first study hinting at the genetic underpinnings of tail loss and is vastly important in understanding human evolution.

Edited by Jayati Sharma (she/her)

Leave a comment