A recent study by Salapa et. al. published in Nature Communications found that a protein called hnRNP A1, which helps process cellular RNAs, can become dysfunctional and contribute to neuron death in multiple sclerosis. This is the first time that a protein that interacts with RNA has been linked to this disease, which brings MS into the fold of the many neurodegenerative diseases that are associated with RNA-binding protein (RBP) dysfunction, providing a new potential avenue for therapeutic research.

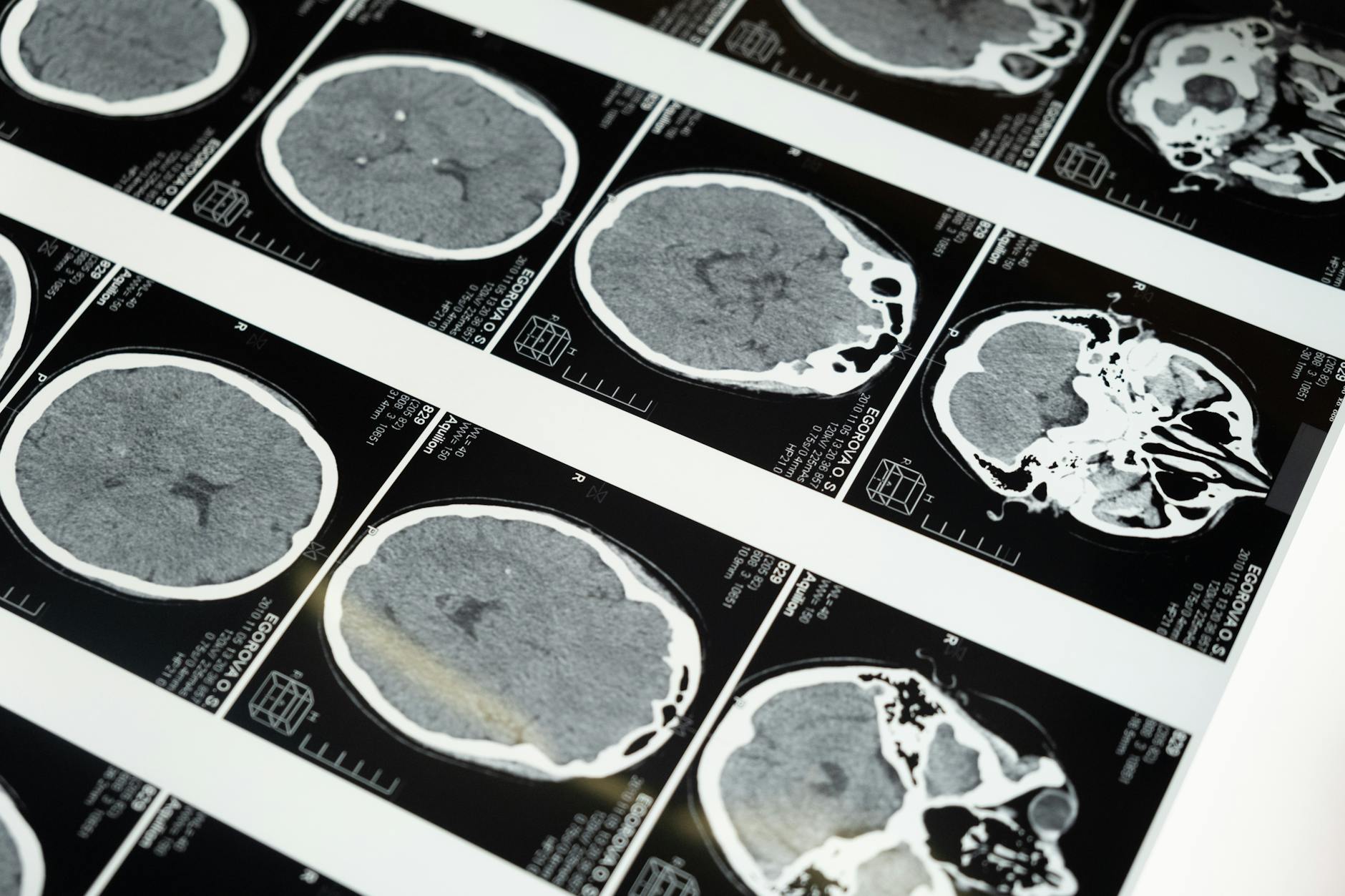

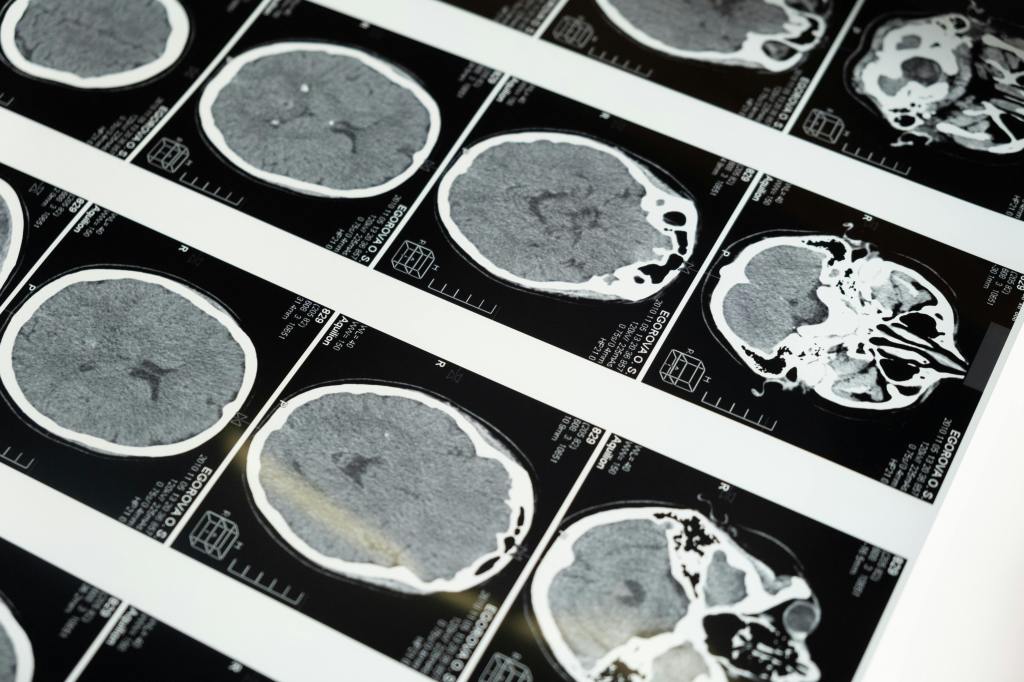

Multiple sclerosis (MS) is a disease where inflammation caused by the immune system leads to a reduction in the protective insulation on neurons. This ultimately results in neurons dying, and symptoms including vision problems, lower limb weakness, and cognitive issues. Both environmental and genetic factors likely lead to development of MS. Data from 2019 and 2020 suggests that MS affects ~2.8 million people across the globe, and although treatment options have expanded in recent decades, they are still not universally available, especially for certain subtypes of the disease.

MS is one of many neurodegenerative diseases (diseases involving the death of cells in the nervous system) that can greatly impact the people who develop them. If we zoom in to the cellular level, one common problem in several neurodegenerative diseases is faulty proteins that bind to RNA. RNA molecules can carry genetic information and can be used to carry recipes for proteins out of the cell nucleus to other parts of the cell. RNA-binding proteins (RBPs) usually help RNAs become processed normally and help the RNAs go where they’re needed. In disease, these RBPs sometimes end up in the wrong location, which can prevent them from doing what they’re supposed to, or in some cases, can allow them to actively cause problems in cells, like in Alzheimer’s disease and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis.

Previous research on MS has suggested that RNA processing and RBPs may be involved with the disease, but the specifics had not yet been discovered. For example, the lab that performed the current study also previously found that mouse and cell models, as well as brain cortices from MS patients, display dysfunction of an RBP called hnRNP A1. Since RBP dysfunction is common among other diseases where neurons die, the laboratory wanted to figure out what hnRNP A1 dysfunction was doing in MS.

In order to study the details of how diseases progress and cause problems, scientists need to rely on model systems, since we can’t conduct experiments in live people. Here, the researchers used a mouse model called experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis (EAE), which recapitulates some of the symptoms of MS, and neural cell models to study various aspects of the role of hnRNP A1 in MS.

They saw that in many of the MS brain cells, hnRNP A1 proteins were in the wrong place, so they took the RNA from MS brain cells to look at what genes were being used in the cells. They found that there wasn’t a significant change in how much the hnRNP A1 gene itself was being used. However, the majority of genes that were used more or less than in normal brains yield RNAs that usually interact with hnRNP A1 protein, suggesting that the protein’s mislocalization could be related to the altered prevalence of those RNAs.

The researchers then used an experiment called CLIP-seq to figure out what specific RNAs were interacting with hnRNP A1 in the spinal cord of EAE mice. They found that in mice with severe EAE, hnRNP A1 interacted with RNAs from fewer genes compared to healthy or mild EAE mice. Many of the genes whose RNA no longer interacted with hnRNP A1 in EAE mice are involved with neuronal functions. This suggests that neuronal functions may be impacted, which could be directly studied more in future research.

So, why does it matter which RNAs are interacting with hnRNP A1? Well, interacting with the RNAs allows hnRNP A1 to impact a step of their processing called splicing. RNAs can be spliced in different ways (i.e. alternative splicing), which can affect the final protein recipe, and therefore potentially impact how the protein product can act in the cell. Alternative splicing can be studied using RNA-sequencing data and follow-up experiments to look at particular splicing events. The researchers found changes in alternative splicing in their various experimental models. Notably, they found a splicing event that changed similarly in both MS brain tissue and the EAE mouse model in a gene (Macf1) that’s known to be important for neurons and has been associated with neurodegenerative disease .

The researchers then used mutated versions of the Hnrnpa1 gene in non-MS cells to show that this splicing change was an effect of hnRNP A1 dysfunction rather than a different feature of MS. The researchers also found that introducing mutant Hnrnpa1 into neurons led to shorter neurites, which are extensions needed for the cells to receive and send signals. Together, these experiments suggest a path forward for future studies investigating whether fixing the hnRNP A1 dysfunction can alleviate neuronal problems and MS symptoms.

Due to the scope of the study, the research team was only able to focus in-depth on a few specific splicing events that they found altered with hnRNP A1 dysregulation, leaving several other potential events less explored. Additionally, this study left open questions about the molecular steps leading from the splicing changes to neurological effects–though this may be explored in future studies. Though there is still much more to learn in order to apply this to treating MS, the findings of this study are exciting, as they loop MS into the pool of neurodegenerative diseases with dysregulated RBPs. This research puts us one step closer to understanding the biological mechanisms underlying the life-changing disease of multiple sclerosis.

Edited by Jayati Sharma

Leave a comment