An ant colony has many roles to fill. Scientists found genes that help ants stick to their work schedules, and even change jobs.

Many of us modify our sleep schedules for our jobs or other responsibilities. We know sleep loss can be harmful immediately or in the long-term. But even getting the right amount of sleep on a shifted or irregular schedule can prove detrimental, increasing risk of heart disease, diabetes, and cancer.

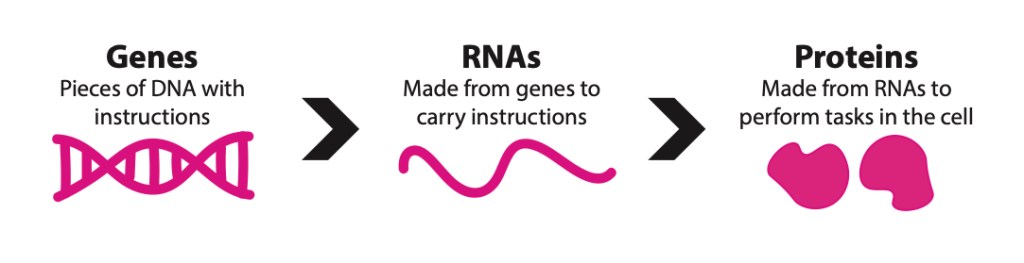

Erratic schedules have such strong impacts on health because staying up through the night goes against our genetics. The body’s default schedule, known as a circadian rhythm, is governed by a group of genes. Genes produce RNA molecules that then serve as the instructions for making proteins.

For many genes, creating RNA isn’t synced to a particular schedule. However, the genes that control circadian rhythms produce RNA in a 24-hour cycle. Some make more RNA during the day, and others make more RNA at night. The resulting proteins interact with each other, and the patterns of those interactions propagate a 24-hour rhythm of waking and sleeping.

Circadian rhythms are also informed by our environment—cues such as the brightness and warmth of sunlight let our bodies know it is daytime. These signals fine-tune the activity of these rhythmic genes. But even without that input, this set of genes would still operate on a 24-hour cycle.

Each species has its own circadian rhythm, despite experiencing the same daily rotation of the earth. Some species’ clocks are tuned for nighttime activity, like in racoons or bats. Other clocks are balanced differently, such as in elephants who thrive on a mere 2 hours of sleep.

Even in the extremes, circadian rhythms are governed by the same set of genes. One of the key genes of this rhythm was found when scientists discovered a mutant fly that was active at all hours. This fly’s schedule was an anomaly for its species, but some social insects like ants and bees keep erratic schedules to help their colonies.

In a study recently published in BMC Genomics, Biplabendu Das and Charissa de Bekker at the University of Central Florida sequenced the RNA from ant brains throughout the day. These researchers explored whether the amount of certain RNAs change with the ants’ daily activity. And while we humans sometimes fight against our genetically ingrained rhythms for our responsibilities, the rhythms of RNA in ant brains aligned with the schedules of their specific jobs.

It Takes a Colony

The most striking division in ant society is that between the queen and her workers, but there are also subdivisions among the workers. Worker ants have the genes to do any job, but ants use their genes differently according to their role.

Two major worker ant categories are the foragers and the nurses. As their name suggests, foragers find food for the colony, and are thus the ants you may encounter out and about. On the other hand, nurses remain in the colony to tend to the young, and with these roles come very different schedules.

The ants the researchers studied are nocturnal. Unaware they were living under the artificial lights of a lab, the foragers came out in the 12 hours the lights were off, and retreated for the 12 hours when they were on, just as they would respond to the sun in the wild. When the researchers looked at the RNA in the foragers’ brains, they found a set of RNAs that cycled in a 24-hour pattern, much like the RNAs that control our rhythms.

However, in their roles as caretakers, the nurses stay inside their dark nest and live on erratic schedules. According to their brains, the nurses’ “around-the-clock” lifestyle is biological. While the RNA in the nurses’ brains didn’t have a 24-hour pattern, they hadn’t entirely lost their rhythm either. Some of the same RNAs had a rapid 8-hour pattern instead.

Changing Careers

The researchers proposed that this fast rhythm may be kept in reserve, ready to bring the nurses to a 24-hour schedule at a moment’s notice. Nurses and foragers are both necessary for survival of the colony, but sometimes the needs of the colony change. When required, nurse ants quickly adopt the lifestyle of foragers, and for that they must alter their biology—and fast.

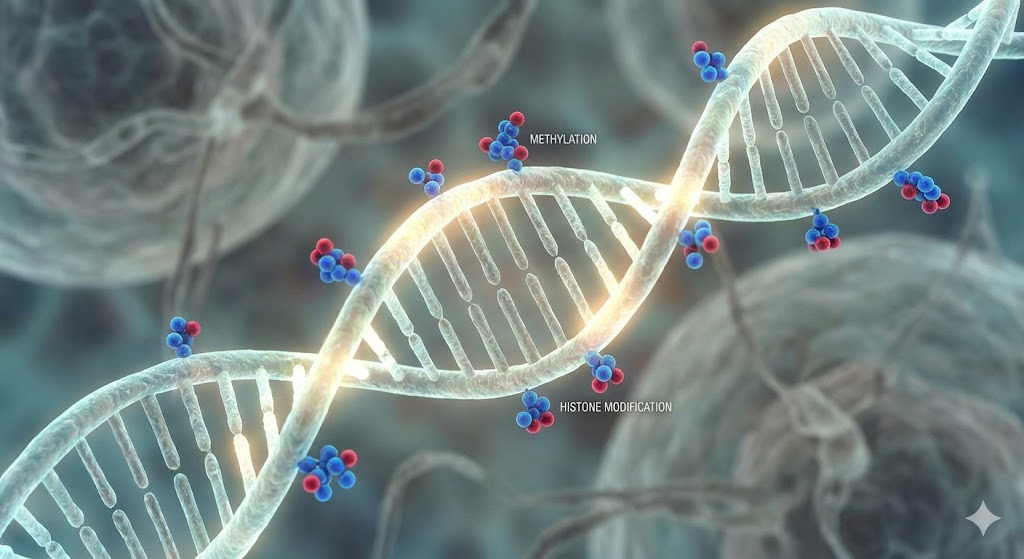

Genes in any organism can be turned “off” and turned “on”, usually by adding and removing chemical modifications to the DNA. When “off”, a gene ceases to make RNA, and thus the protein from that RNA is no longer produced.

Flipping these chemical switches for certain genes allows nurse ants to become foragers. However, a circadian rhythm is a complex interaction between many genes, and thus many switches would need to be flipped in specific ways to turn on a circadian rhythm.

The 8-hour pattern of RNAs in nurse ants led the researchers to suppose that a circadian rhythm isn’t easy to start or stop. Instead, it may be simpler to keep the cycle going in the background in nurses, but lengthen the cycle’s timeframe when needed to suit a forager lifestyle.

Time for Caretaking

Though circadian rhythms are the norm among animals (and even present among plants, fungi, and bacteria), nurse ants aren’t alone in their erratic schedules. Penguins, sharks, orcas, migratory birds, and some cave-dwelling animals can all lead rhythmless lives.

In sharks and some other species, around-the-clock activity is tied to their ability to live. Sharks’ gills only work while in motion, so they suffocate if they stop swimming. However, many other species lead rhythmless lives specifically when taking care of young, just like the nurse ants.

Orcas usually only sleep one brain hemisphere at a time, periodically surfacing for air. Still, this pattern of sleeping usually has a daily rhythm. However, after birth, the orca parent and child don’t sleep at all for several months.

We don’t know if these other creatures completely shut off their internal clocks, or if the RNA in their brains cycles at a different frequency like in nurse ants. Animals that can alter their rhythms also raise the question, why can’t we? From studying creatures with shifting clocks, we may better understand how genes control our rhythms, and also how they don’t.

Edited by Maria McSharry

Leave a comment