Marine plankton jigsaw their mitochondrial genes through unknown mechanisms.

Extreme lifestyles of single-celled organisms capture our imagination. Some microbes can live in the saltiest of waters or in high temperatures, defying our idea of a habitable niche. On the other hand, single-celled eukaryotes challenge our conception of what is genetically possible. In a 2020 study published in Nucleic Acids research, Dr. Binnypreet Kaur and colleagues uncovered pervasive fragmentation in the mitochondrial genomes of aquatic, unicellular eukaryotes called diplonemids. These protists, who dwell in fresh and ocean waters, have organelles much like ours. But unlike humans, whose cells work hard to repair and preserve DNA, diplonemids deliberately fracture and reconstruct their mitochondrial genes. How and why they do this is still unanswered.

Despite their range across marine zones, and with an abundance and diversity unrivaled by other eukaryotes, we know very little about diplonemids themselves. An established, yet striking feature of the best-characterized species, Diplonema papillatum, is the architecture of its mitochondrial genome. With about 250 million base pairs, the diplonemid mitochondrial genome is 14 thousand times larger than that of humans. It is the largest genome of any organelle on record.

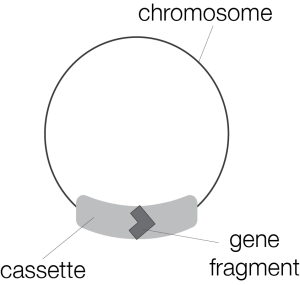

Each of our mitochondria package their genome as a single chromosome containing whole genes. These genes are transcribed from DNA to messenger RNA (mRNA), carefully copying the correct nucleotides (As, Us, Cs, and Gs), to later translate them into proteins. But D. papillatum’s mitochondria take a different approach. Each of their mitochondria contains 81 chromosomes, which house fragments of genes within unique sequences called “cassettes.”

To express a mitochondrial gene, D. papillatum must piece together up to 11 RNAs from different gene fragments in a process known as trans-splicing. Recently, another group of scientists reported even more genetic flexibility in a different species of diplonemid, Hemistasia phaeocysticola. Hemistasia fragments its mitochondrial genome twice as much as D. papillatum and is capable of swapping the nucleotides upon transcribing the mitochondrial DNA to mRNA.

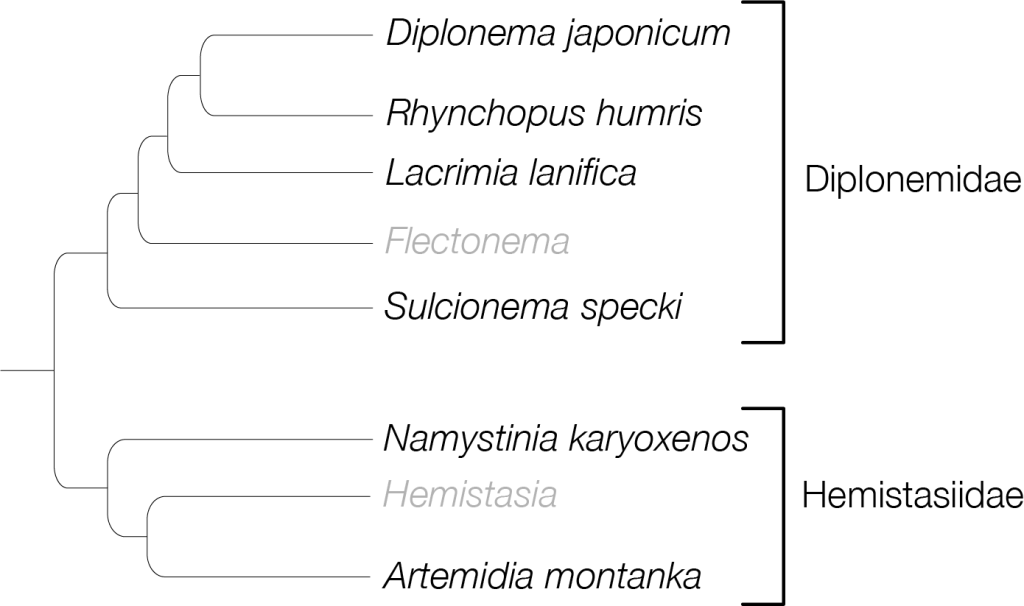

Kaur and colleagues were therefore curious whether the elaborate gene fragmentation and nucleotide swapping seen in H. phaeocysticola is unique. They also wanted to know whether further complex mitochondrial architecture exists in diplonemids. To these ends, they used RNA-sequencing wherein mitochondrial mRNAs were extracted and compared against reference sequences to discover differences in organization across diplonemid species.

By matching stretches of the mitochondria’s mRNA to their DNA, this technique can reveal where the pieces of mRNA came from as well as gene fragment sizes and quantities, and nucleotide edits. They studied the six diplonemid species that can grow in a lab and found that mitochondrial gene fragmentation and mRNA editing occurs in all of them.

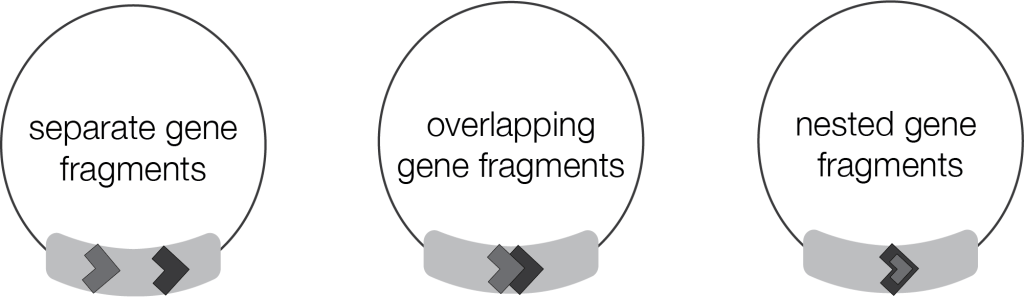

Mitochondrial genomes of the diplonemid species studied are all complex in their own way. They harbor anywhere from 30 to 163 chromosomes and organize gene fragments in myriad ways. Across the diplonemids, researchers typically identified one gene fragment per cassette, though in some cases there were two, or strangely enough, none. And the diplonemid system is further chaotic: gene fragments within species are not evenly distributed. For example, D. japonicum has 23 multi-fragment cassettes and only seven single-fragment cassettes. In contrast, S. specki contains the highest quantity of module-less cassettes, and one cassette that is the most fragment-laden, boasting 11 fragments. The orientation of their mitochondrial gene fragments is creative, too. They may exist as separated sequences, or as overlapping or nested sequences. Diplonemids use gene fragmentation on an unparalleled scale and why they use such a complex schema is puzzling.

In addition to their perplexing mitochondrial gene storage, all six diplonemids can change out mitochondrial RNA nucleotides – a phenomenon not seen in humans. Researchers observed the previously known RNA changes of cytosine to uridine (C to U) as well as adenine to a non-standard amino acid, imine, (A to I) substitutions. They also discovered that, in addition to the nucleotide changes observed in H. phaeocysticola, other Hemistasiidae family members had novel guanine to adenine (G to A) substitutions. We do not know why diplonemids change mitochondrial RNA nucleotides, but their capacity to do so might enable them to make adjustments to gene expression without changing with the mitochondrial DNA blueprint. The modularity of their mitochondrial genome and their ability to edit RNA transcripts could make for an altogether more agile gene expression system than our own.

The diplonemid mitochondrial genome is astounding compared to the animal mitochondrial genomes scientists are more familiar with. As these marine protists bloom into lab organisms, so too does our understanding of their exceptional genetics. We don’t know the machinery required for diplonemids’ trans-splicing or whether a mosaic mitochondrial genome is advantageous, but the convoluted architecture inspires questions like, what else uses a similar strategy? Does this type of modularity allow for novel protein chimeras? Does it allow the mitochondria to compensate in cases where one module is indisposed? Biology can be harnessed for many uses, like DNA replication in PCR or bacterial immunity in CRISPR gene editing. This author, for one, wonders how we might exploit diplonemids’ modular gene system for the benefit of science and medicine.

Edited by Anna Rogers

Source article: Gene fragmentation and RNA editing without borders: eccentric mitochondrial genomes of diplonemids

Leave a comment